Growth is back! After a slower 2022, global recorded music revenues grew by 9.8% in 2023 to reach $35.1 billion, compared to 7.1% in 2022, which means that the market is now more than double (124.5%) the size it was in 2015. 2023 was the year in which the industry settled back into a positive growth trajectory after the volatility of the pandemic and post-pandemic years. But the numbers also point to a market that is embarking on a major period of change.

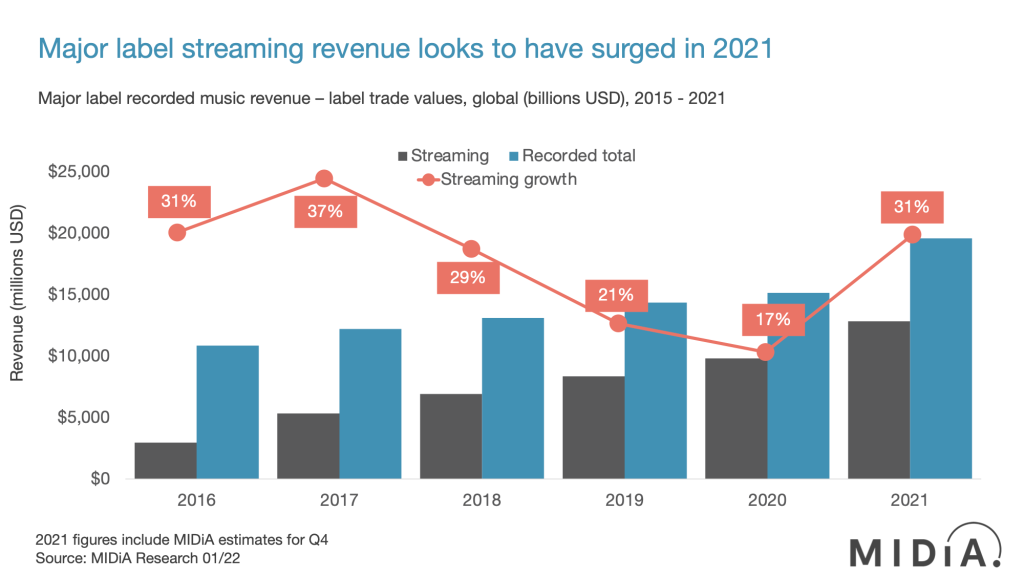

The recorded music market is becoming more diversified, and although streaming is still the centre piece, its role is lessening. Streaming revenues hit $21.9 billion in 2023, up a relatively modest 9.6% on 2022. For the first time ever, streaming grew slower than the total market, to the extent that its share of total revenues actually fell (to 62.5%). Interestingly, over the same period, the five publicly traded DSPs grew revenue by 15.9%, and Warner and Sony collectively grew music publishing streaming revenue by 18.4%. Value is beginning to shift across the streaming value chain.

In other years, the recorded music streaming slowdown would have been cause for concern, but not in 2023. This is because other formats picked up the slack. Physical, after a decline in 2022, was up again (4.6%) in 2023, as was ‘other’. Interestingly, physical is emerging as the industry kingmaker: so far in this decade, over each of the two years that physical revenues grew, industry revenue growth was strong, and in the two years physical fell, industry growth was slow. Physical is the difference between good and great.

The growth in physical revenues, however, is more than just a revenue story, it reflects an industry strategic shift. Anticipating the streaming slowdown, labels and artists alike have been looking for diversification and new growth drivers, with superfans emerging as the central target. The strong growth of physical and ‘other’ revenues in 2023 are the first fruits of the new superfan focus.

The most compelling evidence for the superfan shift, is expanded rights. A subcategory of ‘other’, expanded rights reflect labels’ revenue from sources such as merchandise and branding. In short: superfan formats. Traditionally, expanded rights are not tracked as part of recorded music industry revenues, but last year, because of the industry’s growing fandom focus, we decided we had to include them, even if other entities still do not. 2023 underscored the importance of that decision. Expanded rights revenue grew by 15.5% to hit $3.5 billion – 10% of all global revenues. Expanded rights are one of the main building blocks of tomorrow’s music business.

Change was not constrained to formats. Market shares took some interesting turns, too. Non-major labels had a great year (and we’re calling them that, rather than independents, because a lot of the bigger ‘independents’, such as HYBE, have little in common with what people think of as traditional indies). Non-majors grew revenues by 13.0% in 2023, compared to 9% for the major labels. This meant that non-major label market share was up for the fourth consecutive year, reaching 31.5%. (Though, note this is measured on a distribution basis, not an ownership basis. Therefore, independent revenue that is distributed via a major record label or a wholly owned major label distributor will appear in the revenue of the respective major record label. So ‘actual’ non-major share is higher).

Non-major labels had a great year in expanded rights, outgrowing the market, in large part thanks to Korean labels, which accounted for nearly 70% of non-major label expanded rights revenue.

In stark contrast, 2023 was a tough year for artists direct (i.e., self-releasing artists), with various streaming market developments seeing them grow streaming revenue and their number of streams much more slowly than in previous years. 2023 was the first year artists direct lost market share. Streaming revenue grew just 3.9% in 2023, compared to 17.9% in 2022 and 35.5% in 2021. The result was a 0.4 point decline in streaming market share. Despite a difficult 2023, artists direct revenue in 2023 was 57.7% higher than in 2020, though the impending streaming royalty changes will likely see growth slow further.

On the majors’ side of the equation, Universal remained the largest label group, with its $10.0 billion representing 28.3% market share, but for the first time since 2020, Sony was the fastest growing major, increasing revenues by 11.6%, growing market share 0.3 points to 20.3%

Concluding thoughts

2023 was a very positive year, and it may prove to be the one we look back upon as ‘when things started to change’. Streaming growth slowed, on the recordings side of the equation, at least; monetising fandom became a serious part of the industry; non-majors locked into long-term market share growth; and self-releasing artists started to see a clear divergence between what they streamed and what they earned.

The industry is beginning to bifurcate between the traditional, streaming-focused business, and a new one in which fandom and creation will take centre stage. Welcome to the first year of tomorrow’s music business.

Each of the previous music business eras have been defined by and named after the dominant formats of the time. Industry business models were transformed by these technology shifts and the resulting changes in consumer behaviour. Nevertheless, the underlying relationship between artists and labels remained relatively unchanged, with the label very clearly the senior partner. Now that is beginning to shift. Artists are more empowered and informed than ever because of:

Each of the previous music business eras have been defined by and named after the dominant formats of the time. Industry business models were transformed by these technology shifts and the resulting changes in consumer behaviour. Nevertheless, the underlying relationship between artists and labels remained relatively unchanged, with the label very clearly the senior partner. Now that is beginning to shift. Artists are more empowered and informed than ever because of: