Streaming has come a long way since its days as a pure music service for super fans. Spotify’s announcement that it is making 15 monthly audiobook hours available to premium subscribers is simply the latest step in a journey that has seen streaming become the 21st century’s take on radio. This has been achieved with the steady addition of non-music content (podcasts and audiobooks especially) and a growing emphasis on programmatic lean back consumption. As with all change, when it sits in an extended period of transformation, its immediate impact is often under-recognised. Audiobooks are the completely natural and logical progression for Spotify (and other DSPs), but they are also another waymarker in the journey away from being a pure play music service.

The pandemic was a catalyst for audiobook consumption. Audiobooks had been around for a long time already, with Audible leading the charge, but it was the sudden increase in non-allocated time that people found themselves with that triggered a coming of age for the format. Listening surged, including of podcasts, but as normal life slowly returned, audiobook consumption dipped again, though to a higher point than pre-pandemic levels.

In many respects, Audible never really managed to push the format out of its niche foundations, with weekly active user (WAU) penetration still stuck at around 10% (Q1 23). DSPs though, represent the opportunity to mainstream the proposition – something that Deezer identified many years ago by becoming the first DSP to integrate audiobooks. Deezer was, however, probably a little too early, launching audiobooks when streaming was still almost entirely about music and still very lean-forward. Now, streaming is the soundtrack to our everyday lives. It is about filling the silence (or blocking out the noise) more than active listening. In this use case, spoken word audio is just as good a fit as music. In fact, it can often be a better fit. For example, getting lost in the narrative of an audiobook can make a daily commute fly by a lot quicker than simply listening to a playlist, in large part because it commands your attention.

Spot the important shift there? Audiobooks can turn passive listening into active listening in a way that music cannot so easily do. Music carved out hours for streaming by being passive, and now audiobooks and podcasts can colonise those hours with active consumption. The more active usage becomes, the more engaged a user is and the less likely they are to churn. Music did the hard yards; audio reaps the rewards.

Music rightsholders have long been concerned about audio eating into listening hours, less because of the cannibalisation of hours and more so because of the risk of DSPs using that as a basis for negotiating down the share of the subscription fee that gets paid to them. 15 hours of audiobooks may not sound like a lot but it represents close to 40% of the monthly music listening hours of the average subscriber. There is a good chance that there will be strong uptake, not least because over half of audiobook WAUs are also Spotify WAUs (which will probably give Audible pause for thought).

Of course, from Spotify’s perspective at least, the benefit of reducing music rightsholder fees simply to replace them with book publisher fees would be self-defeating. That is unless Spotify can secure the latter for less. But there is another crucial variable at play: original content. Back in 2020, when Spotify was hiring its head of audiobooks, the job description included the following: “Develop, pitch and oversee production of high-quality content”. Just as with podcasts, audiobooks represent an opportunity for Spotify to develop original content and improve its margins.

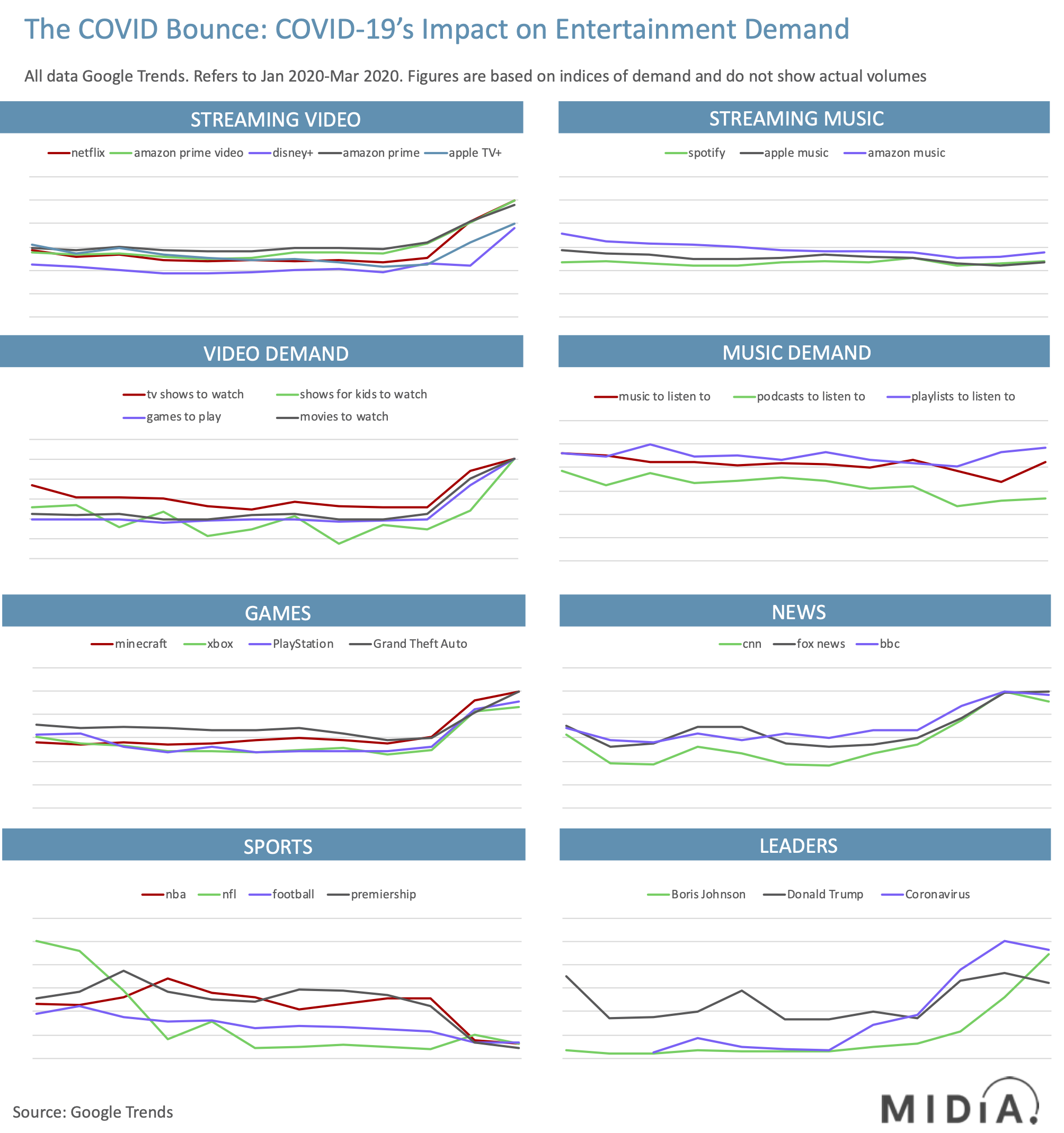

To further illustrate these trends, MIDiA compiled selected Google search term data across the main entertainment categories. The chart below maps the change in popularity of these search terms between the start of January 2020 up to March 27th. Google Trends data does not show the absolute number of searches but instead an index of popularity. These are the key findings:

To further illustrate these trends, MIDiA compiled selected Google search term data across the main entertainment categories. The chart below maps the change in popularity of these search terms between the start of January 2020 up to March 27th. Google Trends data does not show the absolute number of searches but instead an index of popularity. These are the key findings: