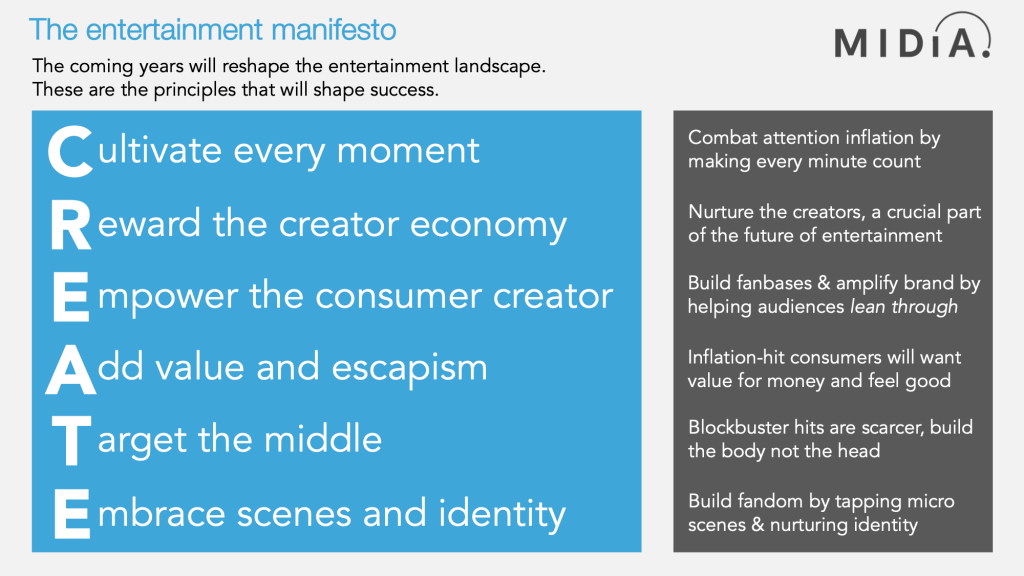

MIDiA recently, and exclusively, revealed that expanded rights now represent 10% of the recorded music market with revenues of $3.5 billion. These revenues, derived principally from monetising the brand of the artist (merch, sponsorships, branding, live, etc.), represent a shift in strategic focus for the global music business. It is moving from a consumption economy to a fan economy. This is only the start. To truly harness the vast potential of a fan economy, three key things need to be addressed:

- Image and likeness: The music industry’s current social media focus might be the UMG / TikTok spat, but the real battle will be over the cultural value of artists on social. As music creators invest increasingly more time into making social content, their images and likenesses are powering social media engagement and revenues. We are at the point where some value exchange needs to be established. Back in 2021, we laid out the case for a creator right (the linked report is free to download) that ensures creators are remunerated whenever they generate value, regardless of whether their music is being performed. With the ascent of generative AI, the concept is needed more than ever. The music business is waking up to the importance of image and likeness. The catalogue deal for Tina Turner included these rights, while Bob Marley’s estate sold his catalogue but retained his image rights because they have used them to create a global Marley branded empire. Likeness rights have a long history, with the first big ‘win’ being actor Crispin Glover settling with Universal Studios in 1990 for infringing his likeness when they altered the appearance of another actor to look like him with prosthetics as George McFly in Back to the Future Part II. This resulted in The Screen Actors Guild prohibiting its members from mimicking other actors. Music needs a George McFly moment. The state of Tennessee protecting artists’ voice and likeness may be a first step.

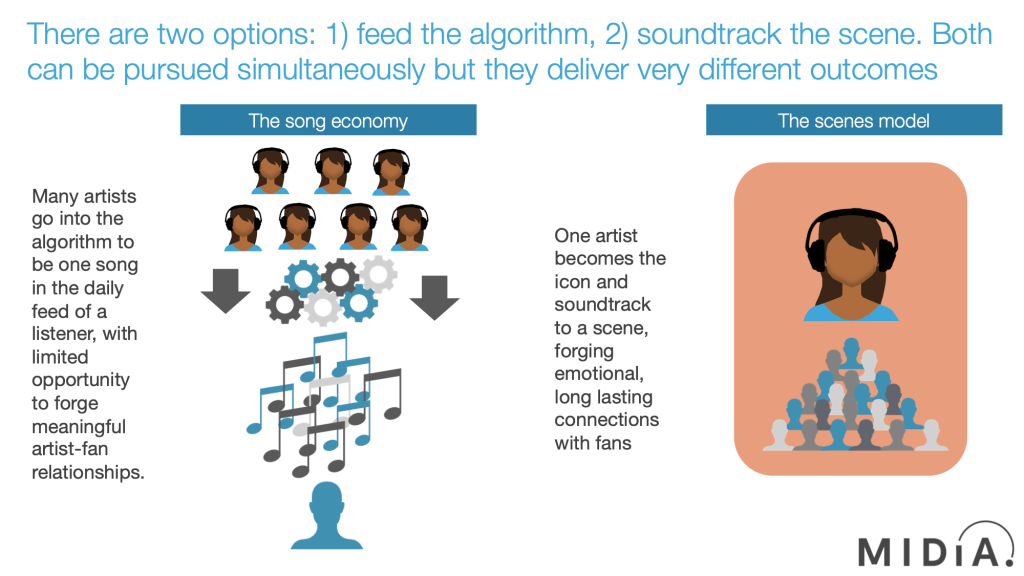

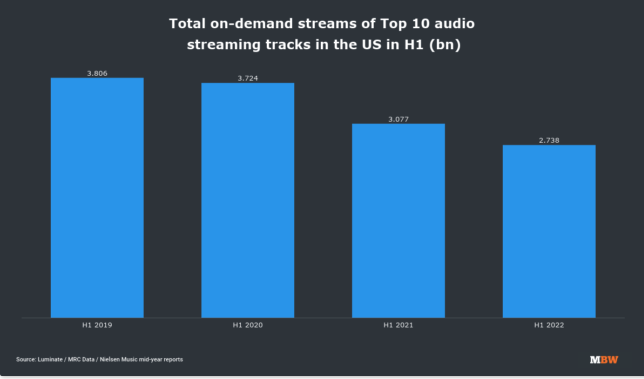

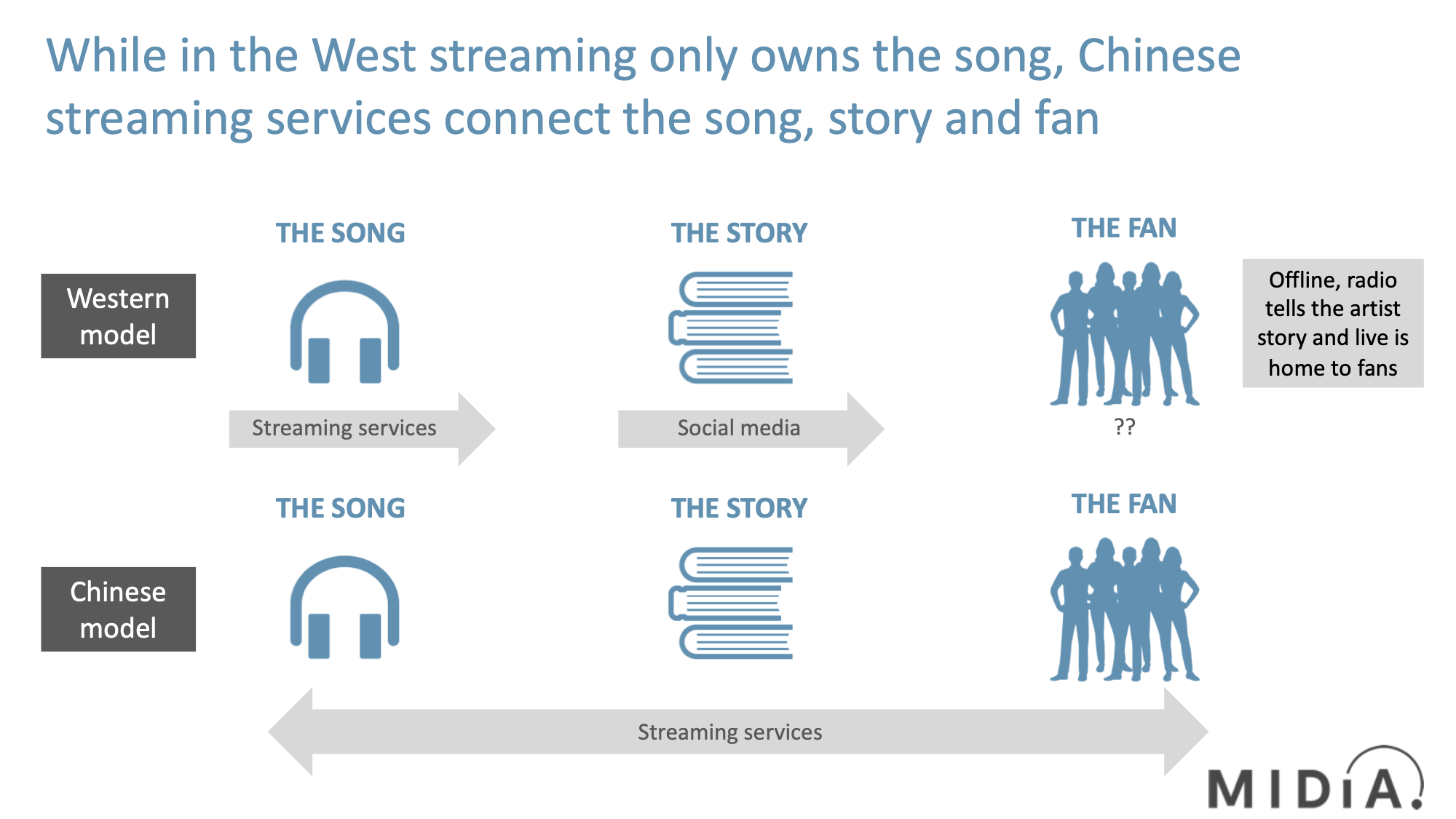

- Reconfiguring streaming: MIDiA has been saying for years now that there is a lot Western streaming can learn from China’s fandom-focused approach to streaming. While Chinese fandom revenues have recently taken a hit due to governmental policy shifts, the underlying premise of making streaming about fandom and expressing identity remains crucial. Artist subscriptions are an obvious next step, making streaming about lean in fandom rather than lean back consumption. We have written about artists subscriptions a lot – recently; more than a decade ago; and in governmental policy submissions. James Blake’s escapes may have soured appetite, but that is, in part, because stand alone subscription apps face an uphill struggle. The most obvious opportunity is to make them part of the core streaming experience. The old internet was ‘build it and they will come’, today’s is ‘go where the audience is’. But there is more to do than artist subscriptions. Giving users profile pages where they can buy and earn fandom badges is probably the most important first step, something pioneered in the West by Audiomack and also seen on apps like Fave and Renaissance. HYBE is prepping Weverse for international expansion, Spotify looks set to make some moves soon, and both Sir Lucian Grainge and Rob Kyncl are leading their respective companies in this direction too.

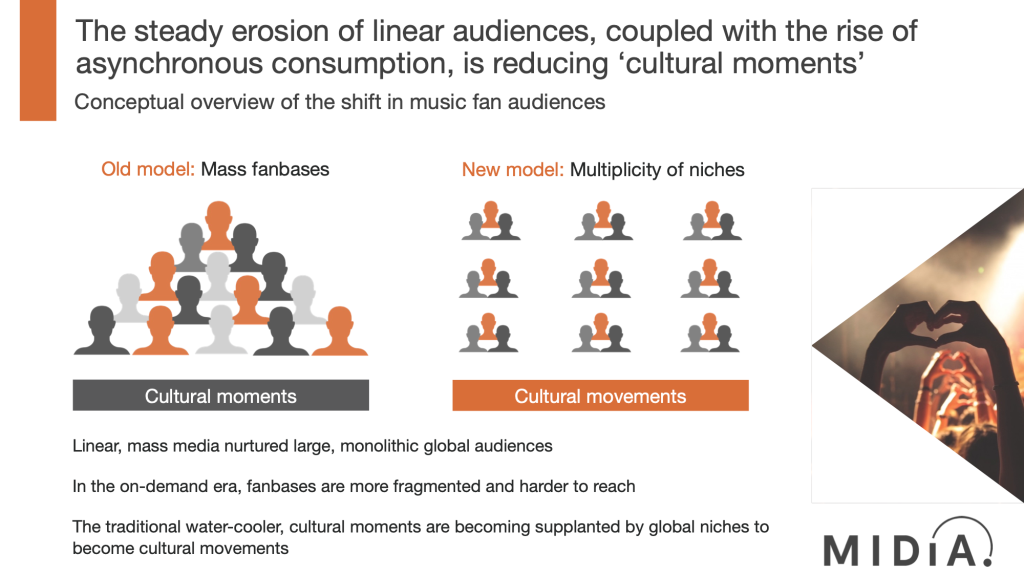

- Nurturing, not harvesting, fandom: There are two dangers inherent in record label superfan strategies: 1) weaned on lean back streaming, superfans might not be super enough, and 2) it is all too easy to focus on monetising fandom rather than nurturing it. As much as Korean labels like HYBE, SM, and JYP might be industrialising fandom and exploiting fans, they at least understand the importance of building and nurturing fandom (take a look at the chart from JYP’s earnings to understand their fandom approach). Record label expanded rights were up 16% in 2023 and will continue to grow strongly. It is incumbent on record labels to consider fans as a scarce resource to be cultivated, not simply monetised, otherwise the soil will be left exhausted and barren.

Along with non-DSP and vinyl, expanded rights represent part of the modern music industry’s multi-faceted fan strategy and 2023 was arguably the first year of this new music business era. Streaming is not going away. Indeed, it will be part of this future, but the consumption-focused approach of the 2010s is going to be shunted to the side as fandom takes centre stage. Not a moment too soon.

I have written a lot in the past about Tencent Music’s portfolio of apps. Alibaba’s Xiami Music is one of the smaller players and its end-to-end value proposition is all the more impressive for that: this sort of functionality is table stakes for competing for audience attention in the Chinese market.

I have written a lot in the past about Tencent Music’s portfolio of apps. Alibaba’s Xiami Music is one of the smaller players and its end-to-end value proposition is all the more impressive for that: this sort of functionality is table stakes for competing for audience attention in the Chinese market.