It is 15 months since the launch of Tidal (which was 2 months after Jay-Z’s Project Panther Bidco bought Aspiro) and it is 12 months since the launch of Apple Music (which was a year after Apple bought Beats Music). The streaming world has changed a lot in that time and both those companies have had a disproportionately large amount on influence on the market’s direction of travel. Their arrivals defined Spotify’s role as incumbent while simultaneously casting Apple and Beats as challengers. They have performed their roles of disruptive entrants well, reshaping the competitive marketplace with a strong focus on brand and artist exclusives. Now reports emerge that Apple is in talks to buy Tidal. First victory in the exclusives war or overspending for market share?

When Is An Exclusive And Exclusive?

In the streaming video world an exclusive means exactly that. If you want to watch ‘House Of Cards’ you need Netflix, if you want to watch ‘Man In The High Castle’ you need Amazon Prime. But in music the rules are far more flexible.

Looking at the flagpole exclusives across Apple Music, Tidal and Spotify, most of these are available on other platforms as downloads, while many are available to stream. For example, Beyoncé’s ‘Lemonade’ is only available to stream via Tidal but was available to download on iTunes within 24 hours of release. Understandably, the exclusive albums of each company’s respective godfather are genuinely exclusive. But Rihanna’s ‘Anti’ was given away by Samsung while Spotify’s rock legends exclusives are streaming only.

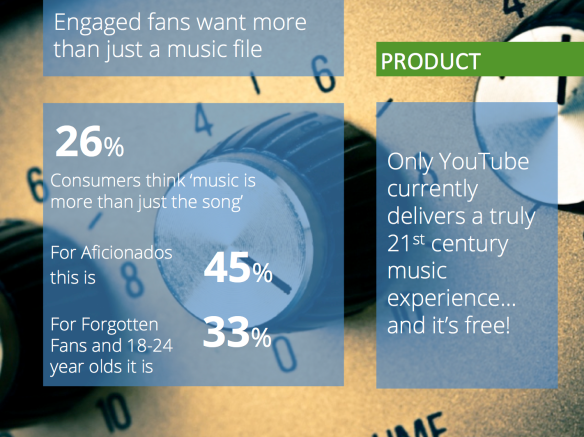

Apple is beginning to push the envelope though, pitching creative solutions to labels and artists, resulting in output like videos for The Weekend and Drake. At the same time it is beginning to look suspiciously like a record label with the release of Chance The Rapper’s ‘Colouring Book’ mixtape. The net result of all this clamouring to be seen as the ‘home’ of an artist is resounding confusion and frustration for music fans. An avid TV fan may well accept the need to have both a Netflix and Amazon subscription because no video service claims to have all the TV shows and movies on the planet. However, the central proposition of streaming music services is exactly that…or at least it was until Tidal and Apple Music upset the the apple cart (ahem). The irony is that in scoring a quick win against Spotify, Tidal and Apple may have fundamentally undermined the long term positioning of the entire streaming music product.

Exclusives Cannot Recreate The 1990s

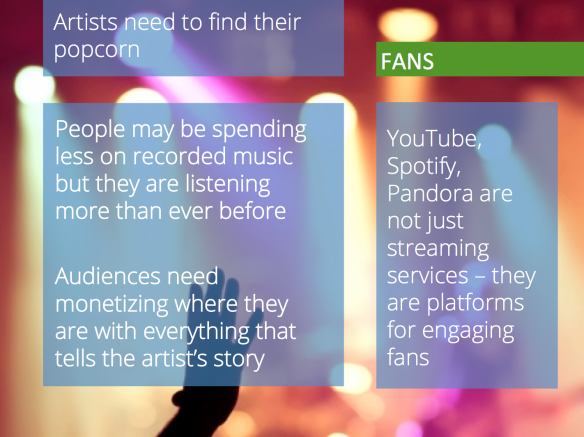

Apple Music’s head of original content Larry Jackson has said he wants to make Apple Music to emulate the success of MTV in the 80’s and the 90’s, creating the sense that artists ‘live there’. It is an admirable goal but the music world of the 2010’s is a dramatically different one. In those days there was scarcity (you had to buy music to listen on demand) and there was a finite amount of radio and TV. It was possible to control both the message and the audience. Now we are in the Era of Distributed Audiences where people are simultaneously in multiple digital places, with artists and labels racing after them in all those places. No amount of exclusive windowing is going to change that. The genie is well and truly out of the bottle.

The Economics Of Exclusives

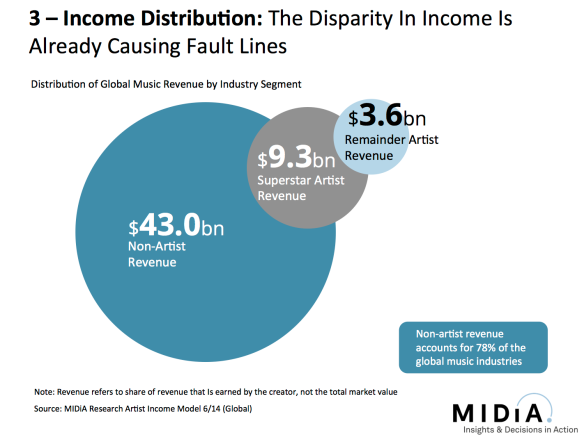

Where the streaming video and streaming music markets match up is that content budgets are currently being used to drive user acquisition. While streaming services have a long way to go before they reach Netflix’s $6 billion annual content budget, both types of streaming service will overspend to get market share and will reel budgets back in later. So it should be no surprise that the amounts being spent on artists don’t really add up.

For example, Apple is reported to have spent $19 million on Drake and was rumoured to have bid up to $25 million for Harry Styles. If Styles had signed, even if he had racked up the same number of streams as Drake on Spotify in 2015 (1.8 billion, the highest number of any artist) he would still only have generated gross revenue of $18 million and net revenue of revenue of around $14 million, leaving something like an $8 million loss for Apple when Apple Music’s additional retailer margin is factored in. Apple would however have been able to make up the remainder on album sales, but Styles would have needed to have shifted a good number of albums. (Adele’s ‘25’, the biggest selling download album in the US in 2015 drove around $15 million in label revenue.) So for now, it takes selling albums to make the economics of streaming exclusives add up.

Jay-Z paid $56 million for Aspiro’s 512,000 subscribers, $110 per subscriber. Assuming he’d want a similar per subscriber price, that would put Tidal’s price tag at around $440 million. That’s no small amount of money for around 5% of the global subscriber market. Or to put it another way, Apple could another 23 Drake exclusives for that money which most likely would have a bigger impact on subscriber growth. Indeed, on all growth measures Apple Music has outperformed Tidal over the last 12 months, adding 12.5 million new subscribers to Tidal’s 3.1 million, growing by an average of 1.4 million subscribers a month compared to 0.3 million for Tidal. Apple even has the edge in % growth terms (352% compared to 328%).

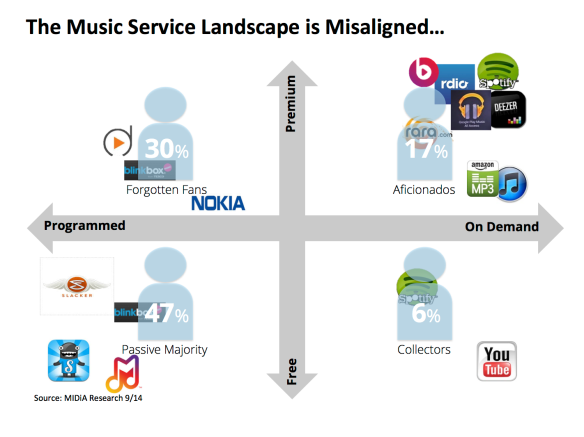

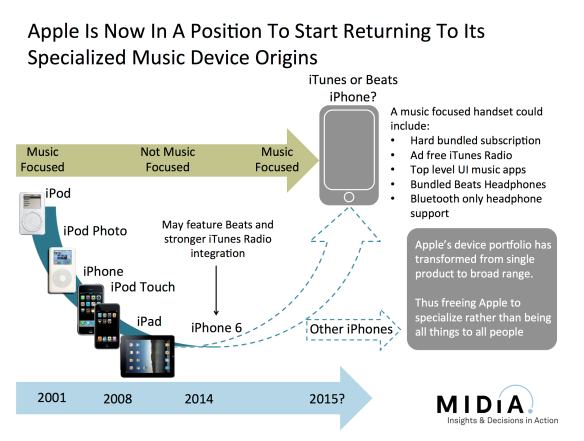

So why is Apple in the market for Tidal (albeit reportedly)? Probably more than anything it is about taking an irritatingly threatening competitor out of the market. Tidal has been stealing Beat’s core customer base from right under its nose. It’s no coincidence that Apple Music’s exclusives strategy has had a strong urban bias. Apple wants its Beats customers back, just like it wants its iTunes customers back from Spotify.

Even if Apple does buy Tidal, don’t expect the exclusives wars to go away. Indeed, Spotify just acquired its own exclusives supremo in the shape of Troy Carter, and Apple clearly has its mind set on continuing to spend heavily. So the next few years of streaming will be defined by streaming services getting closer to artists (with Connect becoming much more important for Apple) which in turn will see the distinctions between what constitutes a streaming service and a record label blur all the more.

As science fiction write William Gibson wrote: the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed yet…