Facebook has announced its long mooted move into music. As widely anticipated the service offering focuses on using music to add context to social experiences. The official blog outlines two key use cases:

- Adding music to videos

- Doing live stream lip syncs in Facebook Live videos

For now the roll out is limited, which will give Facebook the opportunity to hone the service and learn from the behaviour of a relatively narrow user group. A wider roll out will follow.

It’s not about subscriptions, nor should it be

It’s not about subscriptions, nor should it be

Facebook was never going to try be a Spotify clone. Let me rephrase that, just in case anyone in Facebook’s management team is getting tempted to – wrongly – make the wrong move – Facebook should never try be a Spotify clone. Not only is it the wrong fit, it simply doesn’t need to. Streaming music is a low margin business that is being competed over by a number of very well established heavyweights. Facebook may be embarking on a content strategy like the other tech majors, but unlike Apple and Amazon, its core focus will be ad supported, not premium. (MIDiA subscribers – check out our forthcoming inaugural ‘Tech Majors Quarterly Market Shares’ report to see how Facebook’s content strategy stacks up against Apple, Alphabet and Amazon, and where it will be heading.)

YouTube now has a social music competitor worthy of note

For a whole host of reasons which warrant a blog post of their own, streaming music has coalesced around a very functional value proposition. In short, the fun has been taken out of music. Apps like Dubsmash and Musical.ly showed that it doesn’t have to be that way. These apps were small enough to be able to do first and ask forgiveness later. Even though Facebook has all the ingredients to do what those guys did, but at scale, it is far too big to try to get away with that strategy so had to get licenses in place first. YouTube is the only other scale player that really brings a truly social element to streaming. Now it has got a serious challenger that just upped the ante beyond comments, mash ups and likes / dislikes. The music industry so needs this right now. Especially to win over Gen Z.

Is Facebook bottling it when it comes to messaging apps?

For the moment, Facebook’s strategy is squarely focussed around its core platform. There’s no mention of Instagram (surely the best outlet for this kind of functionality). This hints at a degree of strategic wobbles in Facebook towers. By going all in with its messaging app strategy Facebook took a brave move few big companies do: it decided to disrupt itself before someone else did. It realised that the future of social was in messaging apps not traditional social networks. It is now the world’s leading messaging app company, with only Chinese companies truly challenging it (South Koreas’ Kakao Corp, Japan’s Line and Chinese players excepted). But that shift of user time to under monetized ad platforms threatens Facebook’s ad revenue growth. Hence the focus of music to drive usage back to its core platform where it can generate more ad revenue.

Not a Musical.ly killer, at least not yet

Although some have been quick to liken Facebook’s lip sync functionality to Musical.ly and co, in reality it is not competing head on with those apps because it is initially launched as a Facebook Live feature. Betraying Facebook’s strategic imperative of building its Live business. Expect a true Musical.ly ‘killer’ sometime within the next nine months.

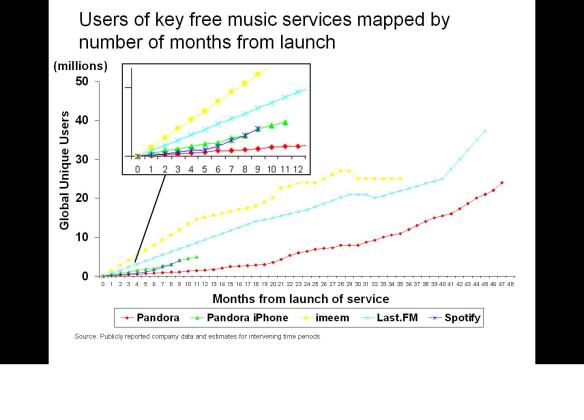

Facebook is not here to compete with Spotify, but it is here to compete with YouTube and Snapchat and to steal some of the clothes of Musical.ly and co. The currently announced features just scratch the surface of what Facebook can do. In many respects music has taken a series of retrograde steps socially speaking since the days of imeem, MySpace and Last.FM. Now Facebook has picked up the dropped baton and is running with it.

Finally for anyone at MIDEM, I will be there from Weds PM to Thursday evening, including doing a keynote Q+A with Napster’s new CEO early Thursday evening. Hope to see you there. My colleagues Zach Fuller and Georgia Meyer are there too, both are speaking, so be sure to say hi.