One of things we pride ourselves on at MIDiA is helping the marketplace peer over the horizon with disruptive, forward-looking ideas and vision. We have a long track record of doing this (you can find a list of report links at the bottom of this post). While many of these ideas were difficult to swallow, or a little ‘out there’ at the time of writing, they became (or are still becoming) a good reflection of where markets ended up heading. Well, it is now time for another of those big market shaping ideas: bifurcation theory.

Today, MIDiA publishes its major new report: ‘Bifurcation theory | How today’s music business will become two’. The full report is available to MIDiA clients here and a free synopsis of the report for non-clients is on our bifurcation theory page here. So, check those out to find more, but in the meantime, here is an overview of just what bifurcation theory is, and why it is going to affect everyone in the music business, whatever role you play in it.

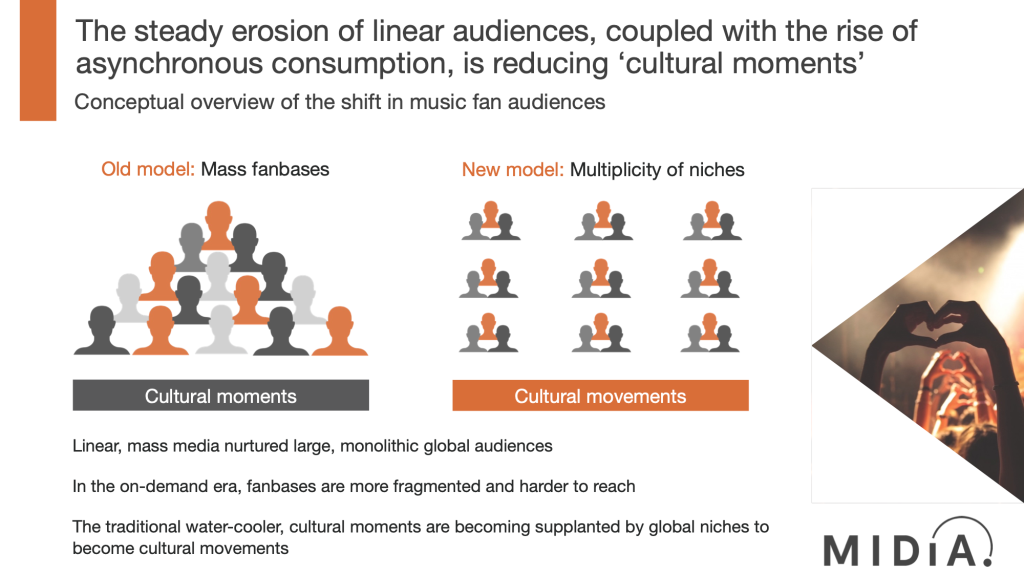

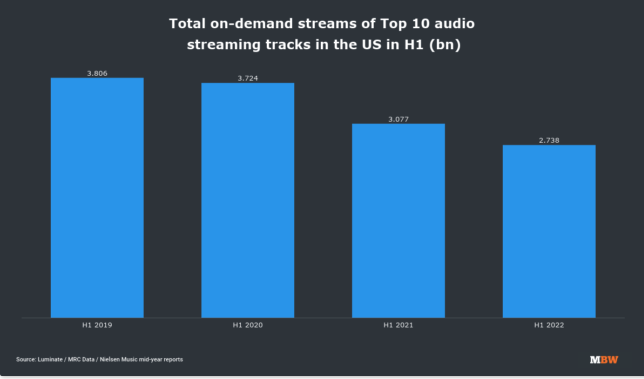

The old maxim that change is the only constant feels tailor-made for the 21st century music business. Piracy, downloads, streaming, and social all triggered music industry paradigm shifts. Now, all the indicators on the disruption dashboard are flashing red once more. AI is, of course, standing centre stage, but it is not the cause of the coming change. It is simply a change enabler.The causal factors this time round are all direct byproducts of today’s music business, unintended consequences of a streaming market that has cantered along its natural path of least resistance. Everyone across the music industry’s value chain has played their role, often unwittingly. Whether that be shortening

songs, increasing social efforts, changing royalty systems or following viral trends, each of these micro actions has contributed to a macro effect.

The fracture points of today’s music business are simultaneously the catalysts for tomorrow’s. For example, the commodification of consumption is resulting in a raft of apps and industry initiatives that try to serve superfans; the rise of the creator economy’s long tail is resulting in both traditional rightsholders raising the streaming drawbridge (long tail royalty thresholds) and a fast-growing body of creators opting to invest less time in streaming.

Streaming was once the future but now it is the establishment, the cornerstone of the traditional music business. It has rocketed from a lean forward, niche proposition for superfans into a lean back, mass market product for the mainstream. Music consumers have always fallen into two buckets:

1. Fans

2. Consumers

The former used to buy music, the latter used to listen to radio. Streaming put them both into the same place, pulling up the average spend but pulling down fandom into consumption. Streaming is the modern day music business’ radio, just much better monetised than the analogue predecessor. Now though, everyone across the music industry’s complex mesh of interconnected value chains is realising there needs to be something more, built alongside, not instead of, streaming. This is the dynamic behind bifurcation theory. This report explores how today’s music business challenges are becoming the causal factors of a new business defined by two parallel consumer worlds.

The music business is bifurcating – splitting into two – with streaming emerging as the place for mainstream music and lean back consumption, and social as the spiritual home of fandom and the creator economy. We identify these two segments as:

1. LISTEN (user-led): streaming services, monetising consumption at scale

2. PLAY (creator-led): highly social destinations where fans lean in to create, connect and express identity

Of course, this process has already started, but social is still largely seen as a driver for streaming. Many artists who try to get their fans to participate on social do so primarily in the hope of driving streams rather than for the inherent value of fans participating in their creativity. However, many next-generation creators are realising they will simply never reach the scale needed to earn meaningful income from streaming.They are therefore shifting focus to building fan relationships on social media and monetising them elsewhere, be it via merchandise or brand sponsorships. Meanwhile, a new generation of fans are creating as a form of consumption, whether that means using songs in their TikTok videos or modifying the audio of their favourite song. While copyright legislation and remuneration have lagged behind these developments, they will be an important part of the future of PLAY. Over time, PLAY will evolve as a self-contained set of ecosystems, built around the artist-fan relationship. It will not be an easy transition. Mainstream streaming will become even more lean back, and social and new apps will exert what will increasingly look like a stranglehold on fandom and the creator economy.

Social apps are plagued with challenges (royalty payments not the least of them) but they will emerge as a parallel alternative to streaming, rather than simply a feeder for it. To this end, the full bifurcation theory report not only describes the lay of the future land, but also presents bold visions of how we think both sides of the music business equation should evolve. We present detailed frameworks for what PLAY services will look like and how LISTEN services can evolve, focusing on core competences to continue to appeal to the mainstream but also deepen appeal to – and better monetise – superfans.

AI will play a key role in the future of both sides of the bifurcated music business, but rather than being tomorrow’s business, it will act as an accelerant for the underlying dynamics of bifurcation theory.

Bifurcation is such a big concept with so many layers and nuances, we have only been able to skim through some of the highest level trends here. We encourage you to check out the full report and report synopsis to learn more.

We’ve spent a long time gestating this concept, so we’d love to hear your thoughts. We’re not expecting bifurcation theory to be to everyone’s taste, but if nothing else, hopefully it will spark some creative thinking and debate.

Don’t forget to check out our bifurcation page for a video discussion of bifurcation theory and a free pdf report synopsis.

As mentioned above, here are some of MIDiA’s most impactful future vision reports, in (roughly) chronological order:

Agile Music (Free report)

Music Format Bill of Rights (Free report)

Rising Power of UGC (Free report)

Independent Artists (Free report)

Rebalancing the Song Economy (Free report)

Scenes – a New Lens for Music Marketing

Creator Rights (Free report)

Fan Powered Royalties (Free report)