Unless you have been hiding under a rock this last couple of weeks you’ll have heard at least something about the build up to the decision over turning net neutrality in the US, a decision that was confirmed yesterday. See Zach Fuller’s post for a great summary of what it means. In highly simplistic terms, the implications are that telcos will be able to prioritize access to their networks, which could mean that any digital service will only be able to guarantee their US users a high quality of service if they broker a deal with each and every telco. As Zach explains, we could see similar moves in Europe and elsewhere. If you are a media company or a digital content provider your world just got turned upside down. But this ruling is in many ways an inevitable result of a fundamental shift in value across digital value chains.

Although the ruling effectively only overturns a 2015 ruling that had previously guaranteeing net neutrality, the world has moved on a lot since then, not least with regards to the emergence of the streaming economy across video, music and games. In short, there is a lot more bandwidth being taken up by streaming services and little or no extra value reverting to the upgraded networks.

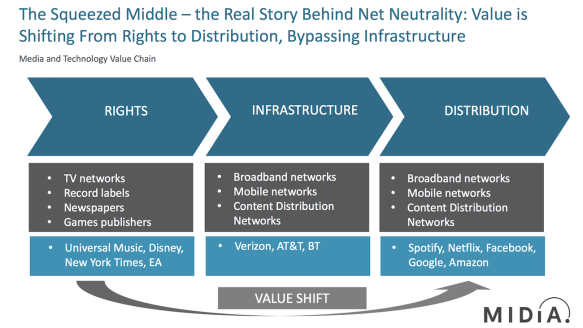

Value is shifting from rights to distribution

Although the exact timing with the Disney / Fox deal (see Tim Mulligan’s take here) was coincidental the broad timing was not. The last few years have seen a major shift in value from rights companies (eg Disney, Universal Music, EA Games) through to distribution companies (eg Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Spotify) with the value shift largely bypassing the infrastructure companies (ie the telcos).

The accelerating revenue growth and valuations of the tech majors and the streaming giants have left media companies trailing in their wake. The Disney / Fox deal was two of the world’s biggest media companies realising that consolidation was the only way to even get on the same lap as the tech majors. They needed to do so because those tech majors are all either already or about to become content companies too, using their vast financial fire power to outbid traditional media companies for content.

The value shift has bypassed infrastructure companies

Meanwhile telcos have been left stranded between rock and a hard place. Telcos have long been concerned about becoming relegated to the role of dumb pipes and most had given up any real hope of being content companies themselves (other than the TV companies who also have telco divisions). They see regulatory support for better monetizing their networks by levying access fees to tech companies as their last resort.

In its most basic form, this regulatory decision will allow telcos to throttle the bandwidth available to streaming services either in favour of their favoured partners or until an access fee is paid. The common thought is that telcos are becoming the new gatekeepers. In most instances they are more likely to become toll booths. But in some instances they may well shy away from any semblance of neutrality. For example, Sprint might well decide that it wants to give its part-owned streaming service Tidal a leg up, and throttle access for Spotify and Apple Music for Sprint users. Eventually Spotify and Apple Music users will realise they either need to switch streaming service or mobile provider. Given that one is a need-to-have, contract-based utility and the other is nice-to-have and no contract and is fundamentally the same underlying proposition, a streaming music switch is the more likely option. Similarly, AT&T could opt to throttle access for Netflix in order to give its DirecTV Now service a leg up. Those telcos without strong content plays could find themselves in the market for acquisitions. For example, Verizon could make a bid for Spotify pre-listing, or even post-listing.

The FCC ruling still needs congressional approval and is subject to legal challenges from a bunch of states so it could yet be blocked. If it is not, then the above is how the world will look. Make no mistake, this is the biggest growing pain the streaming economy has yet faced, even if it just ends up with those services having to carve out an extra slice of their wafer-thin margins in order reach their customers.

For a brief moment last year, windowing seemed like the future of music streaming. Already common practice in the film-industry, the strategy was being touted as a way of utilising artist fan engagement to drive registrations (both freemium and paid) to streaming services, thus engendering the payment behaviours that would ultimately grow the industry. Yet,

For a brief moment last year, windowing seemed like the future of music streaming. Already common practice in the film-industry, the strategy was being touted as a way of utilising artist fan engagement to drive registrations (both freemium and paid) to streaming services, thus engendering the payment behaviours that would ultimately grow the industry. Yet,

One of the themes my

One of the themes my  In 2000 record music represented 60% of the entire music industry, now it is less than 30%. Live is the part that has gained most, and the streaming era artist viewpoint is best encapsulated by Ed Sheeran who cites Spotify as a key driver for his successful live career, saying

In 2000 record music represented 60% of the entire music industry, now it is less than 30%. Live is the part that has gained most, and the streaming era artist viewpoint is best encapsulated by Ed Sheeran who cites Spotify as a key driver for his successful live career, saying