Apple CEO Tim Cook speaks during Apple’s annual Worldwide Developers Conference in San Jose, California, U.S. June 3, 2019. REUTERS/Mason Trinca

Apple has announced that it is closing iTunes and replacing it with three new apps:Apple Music, Apple Podcasts and Apple TV Apps. While this doesn’t (yet) mean the end of the iTunes Storeit is a major development for Apple. In fact, in many ways, it reflects the way in which Apple is becoming ever more later a follower. The great unbundling process has been going on across digital services for years, with Apple the tech major to cling closest and longest to a unified app experience. Now, just as Facebook, Google and Amazon have a suite of specialist apps, so does Apple. Unbundling is a natural part of the digital cycle, giving users the ability have dedicated user experiences that serve specific needs well rather than many (at best) no so well, (at worst) poorly. Indeed Apple’s Craig Federighi’s tongue-in-cheek quip”One thing we hear over and over: Can iTunes do even more?” hints at just how bloated and no longer fit for purpose iTunes had become.

iTunes never did really shake off its origins

iTunes actually started off as a tool for ripping and burning CDs. In fact, its original marketing slogan was ‘Rip Mix Burn’. It evolved into a tool for managing and playing music and supporting the iPod. Over time it layered in videos, books, apps, Apple Music etc etc. But one thing iTunes never excelled on, even before it suffered from feature bloat, was being a great music player. It was if it could never quite shake off its origins. Apple Music has of course picked up the player baton and run with it for Apple. Now that iTunes has splintered into three apps, we should start to see the evolution of three distinct sets of user experiences. Apple hasn’t pushed the boat out yet because it has a fundamentally conservative user base that has to have change implemented at a steady rate in order not to alienate it.

Unbundling and beyond

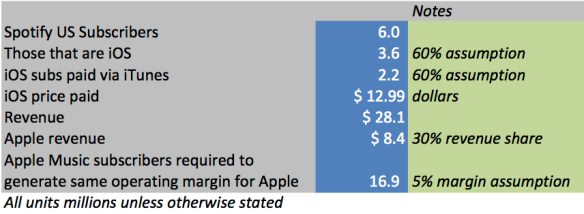

With hardware sales are unlikely to drive strong growth again for Apple until it finds its next big device hit, and although Watch and TV could still both rise to the challenge, it is more likely to be a new form factor. Until then, Apple needs its content and services business to pick up the slack. Right now, the App Store generates the lion’s share of Apple’s content and services revenue and there is clearly an imperative for Apple to ensure that it is driving more revenue from its own products rather than simply extracting a tenancy fee from those of others’. With its new suite of subscription services (Apple Arcade, TV+, News+) Apple is now poised to go deep across a wide range of content offerings. Unbundling its apps and subscriptions gives it the agility to build sector specific user experiences and marketing campaigns. Separating out podcasts is particularly interesting, as Apple is making the call that they do not belong with music. A stark contrast to Spotify’s approach. Indeed, Spotify may just be approaching its own iTunes moment, with an app that is trying to do too many things for too many different use cases. iTunes just committedhara-kirito enable Apple to compete better in the digital content marketplace. Spotify may need to do something similar soon.

Extra little thought: does Apple Music the subscription service now become Apple Music+ in order to differentiate itself from the Apple Music app?

Sonos, granddaddy of the connected home audio marketplace, is now 15 years old. Sonos was a pioneer that was so far ahead of its time, it inadvertently found itself as one of the key early drivers of streaming subscriptions. Visionary founders John MacFarlane and Tom Cullen had some long-term inkling that streaming would eventually be a major force for them, but their near-term vision was built on getting music downloads piped around the home. Now, 15 years on, Sonos has effectively achieved two missions: deploying iTunes around the home, as well as Spotify and co around the home. But now, the outlook is less clear. Sonos’s marketplace is complex and competitive more than ever. Furthermore,

Sonos, granddaddy of the connected home audio marketplace, is now 15 years old. Sonos was a pioneer that was so far ahead of its time, it inadvertently found itself as one of the key early drivers of streaming subscriptions. Visionary founders John MacFarlane and Tom Cullen had some long-term inkling that streaming would eventually be a major force for them, but their near-term vision was built on getting music downloads piped around the home. Now, 15 years on, Sonos has effectively achieved two missions: deploying iTunes around the home, as well as Spotify and co around the home. But now, the outlook is less clear. Sonos’s marketplace is complex and competitive more than ever. Furthermore,