Tencent’s combined $200 million investment in WMG follows on the heels of its $3.6 billion joint investment in Universal Music. It is hardly Tencent’s first investments in music, having spent $6.2 billion on music investments since 2016. But music is just one part of a much larger, supremely bold and undoubtedly disruptive strategy that is making the Chinese company an entertainment business powerhouse in the East and West alike.

Tencent’s combined $200 million investment in WMG follows on the heels of its $3.6 billion joint investment in Universal Music. It is hardly Tencent’s first investments in music, having spent $6.2 billion on music investments since 2016. But music is just one part of a much larger, supremely bold and undoubtedly disruptive strategy that is making the Chinese company an entertainment business powerhouse in the East and West alike.

Tencent is a product of the Chinese economic system

Tencent being a Chinese company is not incidental – it is pivotal. The Chinese economy does not operate like Western economies. Rather than following free market principles, it is a controlled economy in which everything – in one way or another – ultimately comes back to the state. In China, the economy is an extension of the state. The state takes an active role in the running of successful Chinese companies, sometimes very openly, sometimes in less direct ways, such as ensuring party nominees end up in management positions.

Chinese companies are used to working closely with the state – in its most positive light – as a business partner. When a company’s objectives align with those of the state, an individual company may gain preferential treatment at the direct expense of competitors. This is exactly the opposite way in which state involvement happens in the West (or is at least supposed to) – i.e. regulation. Tencent has benefited well from this approach, not least in music.

Tencent Music is the leading music service provider in China (78% market share in Q1 2020) and is also the exclusive sub-licensor of Universal, Sony and Warner in China. This means that Tencent’s streaming competitors have to license the Western majors’ music directly from it. Tencent clearly has a market incentive to ensure terms are less favourable than it receives itself. Netease’s CEO call the set up ‘unfair’ and regulatory authorities are at the least going through the motions of investigating. But the fact this set up could ever exist illustrates just how different the Chinese regulatory worldview is.

Investing in reach and influence

Why this all matters, is that when Tencent views overseas markets it does so with a very different worldview than most Western companies. Taking investments in two of the world’s three biggest record labels might feel uncomfortable from a Western free-market perspective, but to Tencent it just makes good business sense to have influence over as much of the market as it can get. What better way to help ensure you get good deals in the marketplace? Such as, for instance, exclusive sub-licensing into China.

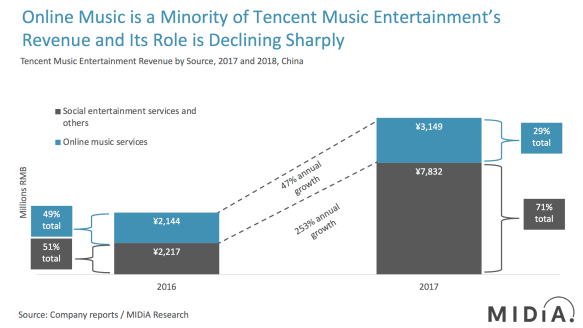

Music is not Tencent’s main priority. For example, its combined $6.2 billion spent on music investments is less than the $8.6 billion that Tencent spent on acquiring 84% of gaming company Supercell in 2016). Nonetheless, music – along with games, video, messaging and live streaming – is one of the central strands of Tencent’s entertainment portfolio strategy.

Just as Apple, Amazon and Alphabet are building digital entertainment portfolios designed to compete in the ‘attention economy’, so is Tencent. In fact, it is fair to say that Tencent is prepping itself as a direct competitor to those companies. But while each of the Western tech majors compete in familiar (Western) ways, Tencent is taking a more Chinese approach.

If you don’t like the rules of the game, play a different game

Tencent’s entertainment investment strategy can be synthesised as follows:

- Take (predominately) minority stakes in companies to get the benefit of influence without having to shoulder the burden of ownership

- Invest end-to-end across the supply chain, from rights through to distribution

- Systematically invest in direct competitors so that they are all each other’s enemies but are all Tencent’s friend

This strategy has given Tencent access to and / or control of:

- Audience (e.g. QQ, WeChat, Weibo, Snapchat (12%), Kakao (14%), AMC Cinemas – via its stake in Wanda Group),

- Distribution (e.g. Tencent Music, Tencent Video, Tencent Games, Joox, Spotify (10%), Gaana, KuGou, Kuwo, QQ Music, Tencent Video, Tencent Games, Epic Games (40%)

- Rights (e.g. UMG (<10%), WMG (1.6%), Skydance (5%–10%), Supercell (84%), Glumobile (15%), Activision Blizzard (5%), Ubisoft (5%), Tencent Pictures)

The Western tech majors have built similar ecosystems, acquiring the audience and distribution parts of the supply chain (e.g. iOS, YouTube, Instagram, Twitch, Apple Music) but only rarely getting into rights (e.g. Apple TV+ originals) and never systematically investing in competing rights holders.

The Western tech majors may have often tetchy relationships with rights holders but their strategic focus (for now at least) is to be partners for rights holders. Tencent’s strategy is one of command and control: vertical supply chain integration secured through the sort of behind-closed-doors influence that billions of dollars’ worth of equity stakes get you.

Tencent may be the future of digital entertainment

Tencent is building the foundations of being one of – perhaps even the – global digital entertainment powerhouse. By taking stakes in two of the Western major labels, Tencent broke the unspoken gentleman’s agreement that streaming services and rights holders would remain independent of each other in order to ensure the market remains open and competitive. Now the Western tech majors have to choose whether to continue playing the old game or to get a seat at the table of the new game. Back in 2018 MIDiA predicted that over the coming decade Apple, Amazon or Spotify would buy a major record label. Maybe that prediction is not quite so outlandish anymore.