MIDiA has been building global music forecasts for nearly a decade now, and I personally have been building them for nearly two decades. Throughout those years there have been many calls for the numbers to be bigger and bolder. Experience, though, has shown that realism most often trumps optimism.

The simple truth is that there are no facts about the future. Instead, forecasts are, at least in MIDiA’s worldview, a structured, numerical representation of analyst thinking. We do not aspire to be cheerleaders for any market, however much we may believe in it. Instead, we strive to be trusted partners, aspiring to provide a view of where things are most likely heading.

With those health warnings out of the way, I am proud to announce the ninth edition of MIDiA’s global recorded music forecasts (If you are a MIDiA client, you can find the report and the 38 sheet Excel data set here).

How we did

To start, I think it is worth a quick look back at how we have done over the years. In our first edition (2015), we forecasted global music revenues (in label trade terms) to reach $20.1 billion by 2020. The actual figure proved to $22.5 billion. So that translates into a 10% variance for a five-year forecast, which isn’t too shabby. Over the course of the previous five years, our forecasts for 2022 had an average variance of -2.5%. Again, a decent track record.

That’s the good news. 2022, though, was an anomalous year, and 2023 is shaping up to be similarly volatile. Shaped as it is, by a cost-of-living crisis, soaring interest rates, economic slowdown, a softening ad market, global food and energy shortages, and a war in Europe. When we built the 2022 edition, we knew these factors might disrupt the music industry’s trajectory, so we built both a base case and bear case forecast. Our base case proved to be too optimistic ($30.7 billion) while our bear case ($28.3 billion) proved to be depressingly precise (just 0.8% above the actual figure of $28.1 billion).

Why currency matters

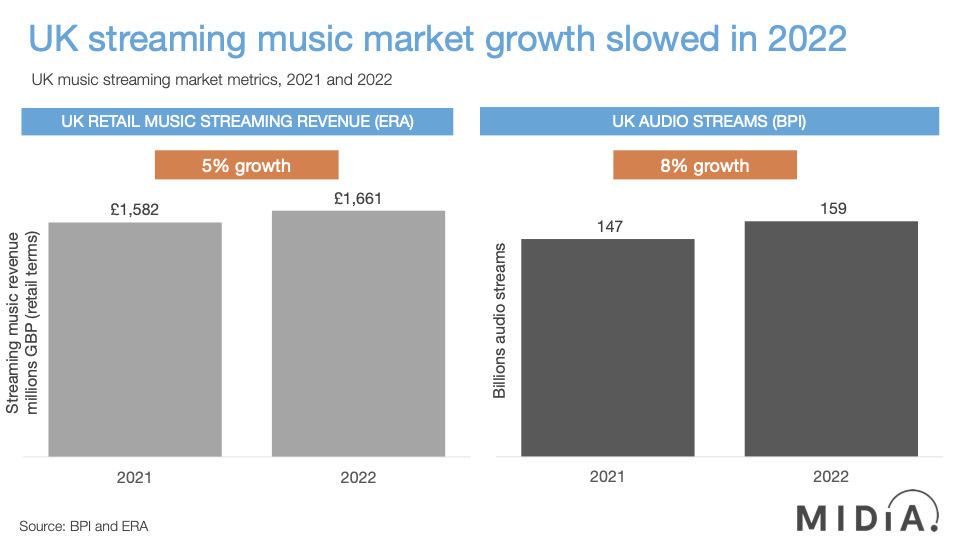

That $28.1 billion represented just 3.2% growth on 2021 – the slowest growth since the global market return to growth in 2015. On the surface, this might look like serious cause for concern, evidence of the long anticipated streaming slowdown. But, while a streaming slowdown is indeed happening, it is only a minor contributor to the bigger picture. Not only is 3.2% respectable growth in the midst of economic and geo-political chaos, currency volatility has, to put it bluntly, played havoc with the global picture.

MIDiA always builds its market models with US dollar values and, crucially, in current currency terms. Simply put, that means the values we present for any historical year represent what the market was actually worth in that year. In a year of global currency volatility, this means that some markets that reported strong growth in local currency terms saw much weaker, sometimes even negative, growth in US dollar terms. It is an analytical inconvenience but, in our view, a necessary one to present a meaningful and accurate view of global value.

Other entities try to mask the inconvenience by restating their entire historical dataset based on the currency conversion rates for the most recent year, i.e., constant currency conversion. Hence, the IFPI reported 9.0% growth in 2022, yet if you compare their 2022 figure to their previously reported 2021 figure, you end up with just 0.9% growth (i.e., a growth rate that is ten times slower). MIDiA’s base case forecast would have looked a lot more optimistic if we had used constant currency conversion rates!

All of these complexities make the job of forecasting particularly challenging. Which is why we focused on more stable metrics, such as local currency values and subscribers, to help us estimate future growth. Subscription revenue grew by just 4% in 2022, but subscribers grew by 16%, illustrating strong, underlying market demand and momentum. However, as is so often the case with market sizing, the picture is more nuanced and complex. Emerging markets grew subscribers far faster in 2022 than North American and European markets, but because they have lower ARPU, the contribution to revenue growth was far smaller.

A decoupling of global growth

What we are seeing is a regional decoupling of global growth, to the extent that the global picture can be misleading. For example, by 2030, there will be 1.1 billion subscribers, up from 663 million in 2022, but Asia Pacific, Latin America and Rest of World will account for four fifths of that growth. Crucially, most Western rightsholders have relatively low repertoire share in much of these regions, so they will not benefit from this next wave of subscriber growth in the same way they did in the first, largely Western, wave.

Yet Europe and North America will account for more than half of the global subscriptions revenue growth, due to higher ARPU and average subscriber months (a result of slower growth). Which means that Western rightsholders will accrue most revenue upside, despite losing out on audience growth.

Growth that is both impressive and eminently achievable

Despite all of today’s market headwinds, MIDiA’s underlying assumptions about long-term growth remain largely unchanged. While we are forecasting slower growth over the next two years, we expect the global market to return to full momentum between mid-2024 and early 2025. This will result in global revenues growing by 51.0% to reach $42.4 billion in trade terms by 2030, and a slightly faster growth in retail terms (due to growing DSP share) to reach $87.1 billion.

As much as we would have liked to report that the market will double in value by 2030, we consider 51.0% growth to be both an impressive performance and eminently achievable. We would have liked to have forecasted a doubling of growth back in 2015 as well, but if we had, we would not have ended up being within 10% of the actual market, half a decade down the line.

The thing about forecasts is they are always updated, so it can be easy to forget anything other than how the latest edition racks up compared to the previous one. Which makes it depressingly easy to build overly-bullish forecasts that have the benefit of aiding ulterior business objectives. MIDiA, of course, has many of the exact same companies as paying clients as the other entities do, but our clients pay to subscribe because they rely on us to provide an objective and useful view of the market. To tell them what they need to hear, even if that is not always what they want to hear.

Spotify announced in its Q3 2019 earnings that 14% of its monthly average users (MAUs) streamed podcasts on the platform during the quarter, representing 33.7 million users and generating $15.9 million.* With total podcast hours up 39% on Q2, there is clearly momentum too – though this growth will be boosted by new podcast users shifting more of their podcast time to Spotify. Spotify has established itself as an important player in the global podcast marketplace but is far from a dominant player yet (it will likely hit 5.5% of global podcast revenue market share by year end 2019). Also, podcasts are still a tiny part of Spotify’s business (just 0.8% of Spotify’s total Q3 2019 revenue).

Spotify announced in its Q3 2019 earnings that 14% of its monthly average users (MAUs) streamed podcasts on the platform during the quarter, representing 33.7 million users and generating $15.9 million.* With total podcast hours up 39% on Q2, there is clearly momentum too – though this growth will be boosted by new podcast users shifting more of their podcast time to Spotify. Spotify has established itself as an important player in the global podcast marketplace but is far from a dominant player yet (it will likely hit 5.5% of global podcast revenue market share by year end 2019). Also, podcasts are still a tiny part of Spotify’s business (just 0.8% of Spotify’s total Q3 2019 revenue).