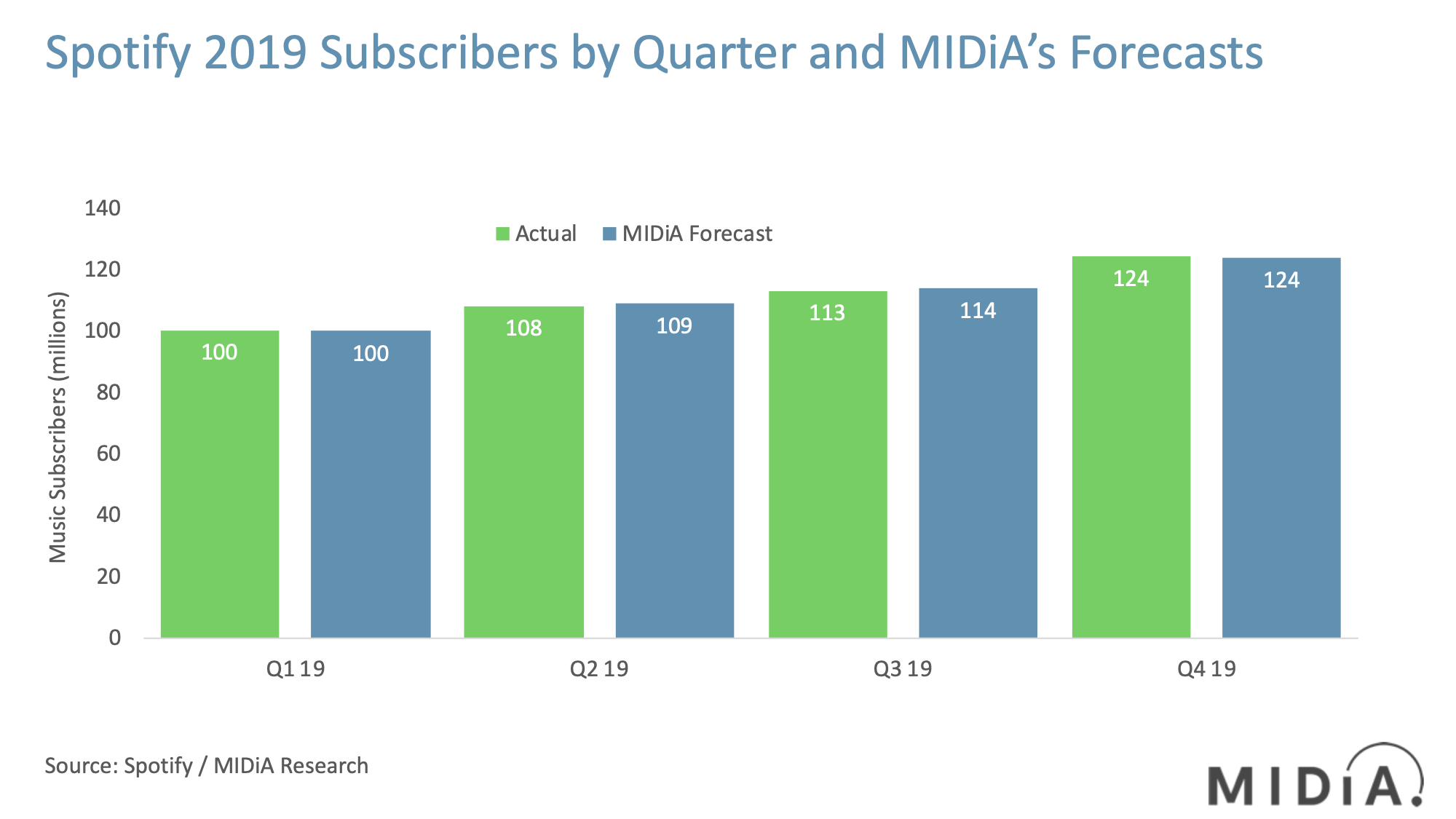

Spotify reported another strong quarter in Q3 2020, with subscriber growth up 27% year-on-year (YoY) and ad-supported user growth up 21%. Spotify continues to set the pace for the global streaming market and has demonstrated that streaming has proven resilient to lockdown. (Spotify finished the quarter with 144 million subscribers, just above MIDiA’s 143 million forecast – we maintain our end of year forecast for 154 million.) Further evidence of Spotify’s lockdown resilience is that global consumption hours surpassed pre-COVID levels and that churn levels fell. However, Spotify’s premium revenue growth continues to trail subscriber increases, which raises the question: what price is growth coming at for rightsholders and creators?

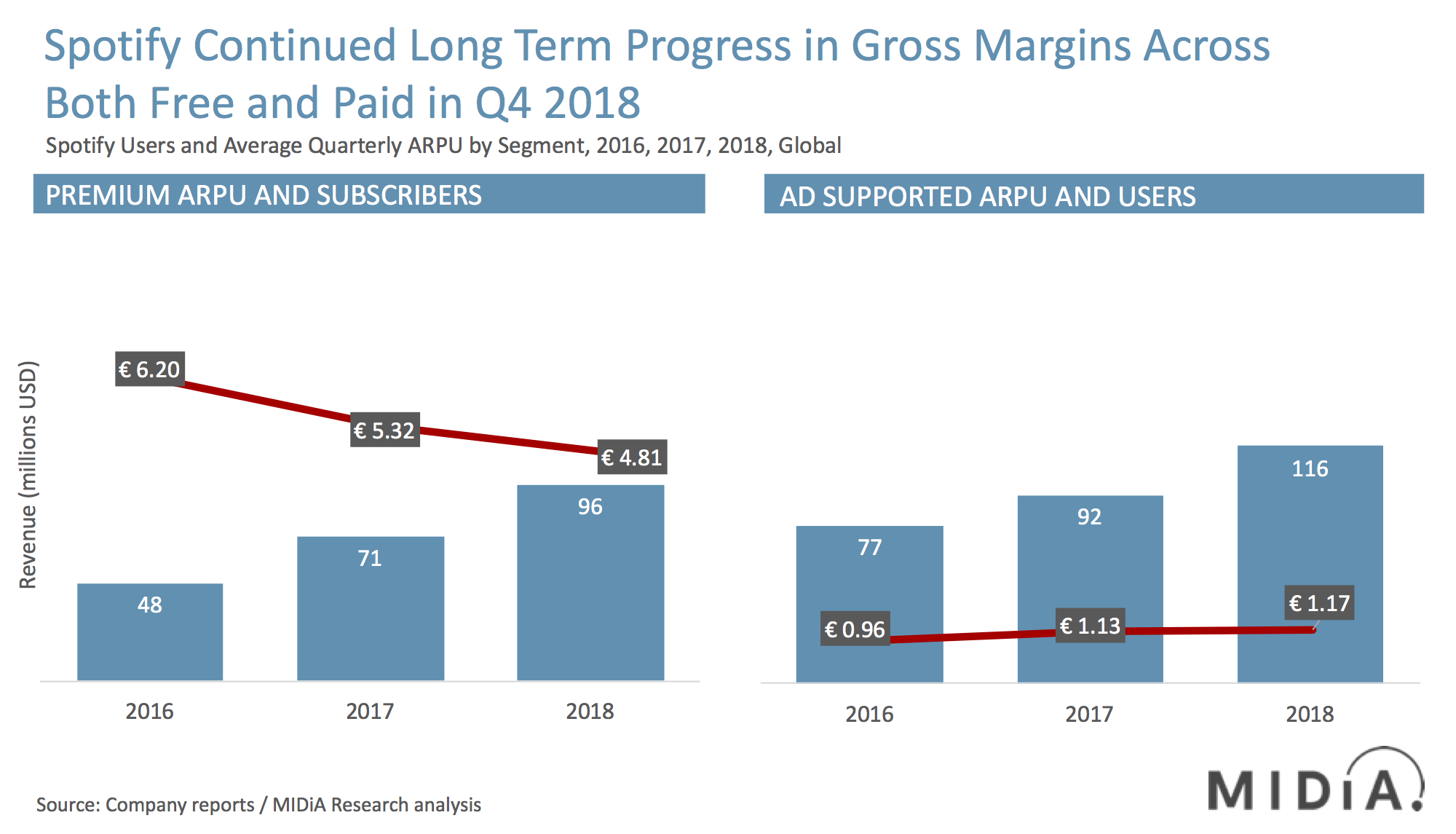

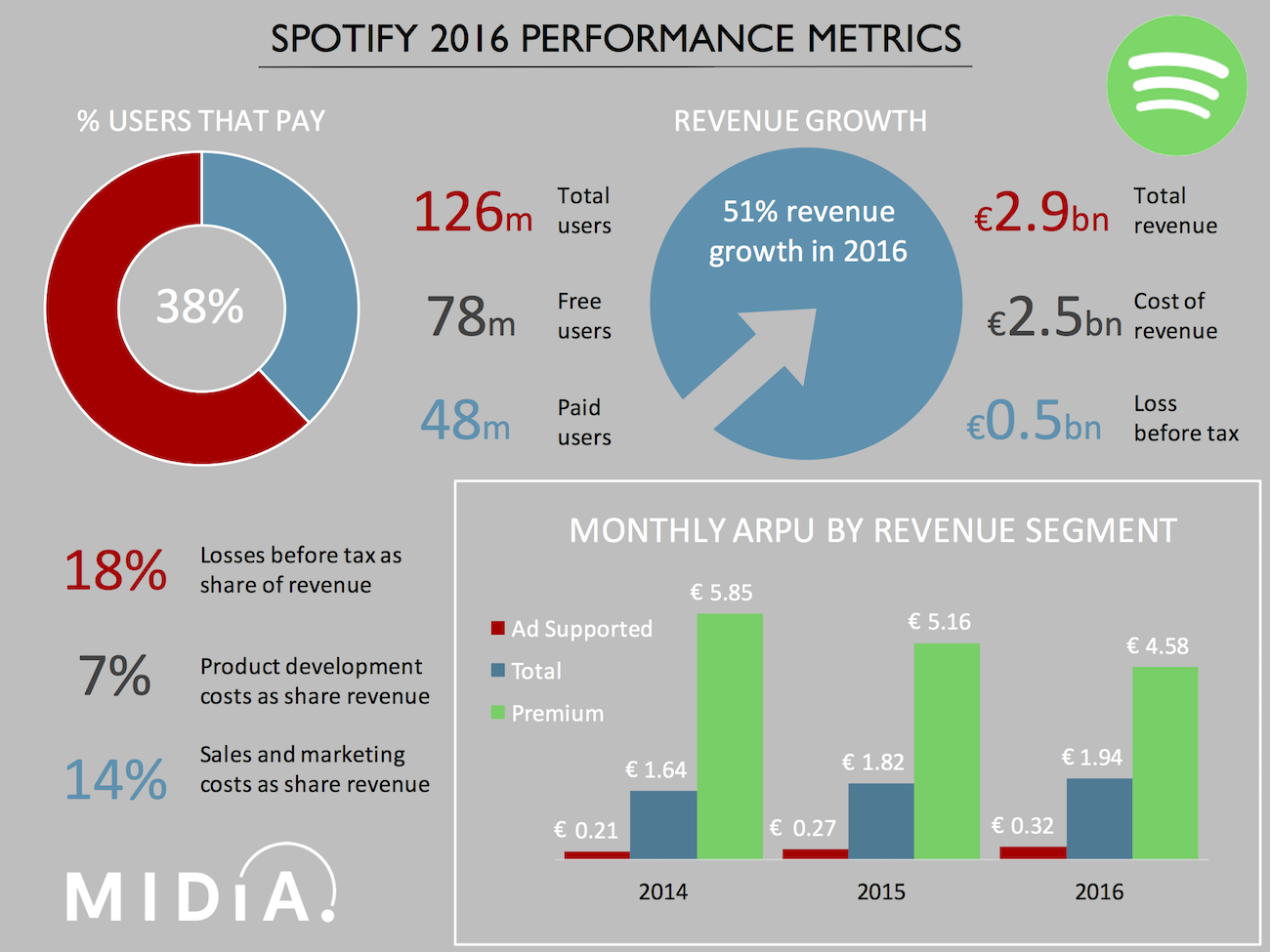

Spotify’s Q3 2020 premium revenue was €1,790 million, up 15% YoY – notably lower than the 27% subscriber growth. This is a long-term trend for Spotify, resulting in a steady erosion of premium average revenue per user (ARPU). Q3 2020 ARPU fell to €4.19, down from €4.67 in Q3 2019 and €5.76 back in Q3 2016.

There are multiple factors underpinning this shift:

Growth of emerging markets where ARPU is lower

Growth of family and duo plans

Use of promotional offers

Growth of low-priced tiers (telco bundles, student plans)

Spotify emphasised that ‘product mix’ was the core driver of lower ARPU in Q3 2020 and pointed to price increases for family plans across four Latin American markets, Australia, Belgium and Switzerland. Rightsholders and creators will be hoping that this is the start of a wider strategy.

‘Measure us on growth’

Spotify continues to tell the markets to measure it on growth and market share rather than margin or ARPU. That serves Spotify better than rightsholders and creators. However, this may be about to change. Spotify’s big growth bet is podcasts, which it is monetising via advertising. Although Spotify had a decent quarter for ad revenue (after many weak ones) it is still just 9% of total revenue. Podcasts have the potential to be bigger than music for Spotify but it is going to take a long time to realise the potential, especially as the coming recession will likely dent the global ad market.

A new growth story

Why this matters for music stakeholders is that Spotify may find it hard to convince investors to start backing yet another ‘measure us on growth’ story when it already has one. As streaming starts to mature in Western markets, Spotify may now be on a path to shift its music subscriptions narrative to one of turning around the ARPU decline, focusing on increasing “lifetime value”, reducing churn and improving margins. It can then make podcasts the ‘growth story’ and music the ‘margin and ARPU story’.

Music rights holders may be concerned that podcasts threaten their share of Spotify revenue, but they may also end up thanking Spotify’s podcasts strategy for indirectly resulting in a stronger focus of improving music monetisation. This in turn will mean higher per-stream rates – something that artists and songwriters in particular will appreciate.