After years of relative stability, music consumption is shifting, with the DSP streaming model beginning to lose some ground as illustrated by the major labels growing streaming revenue by 33% in Q2 2021 while Spotify was up by just 23%. It is never wise to read long-term market trends into one quarter’s worth of results, but there was already enough preceding evidence to suggest we are entering a genuine market shift. The question is whether Spotify and the other Western DSPs are going to find themselves left behind by a fast-changing market, or can they innovate to keep up the pace?

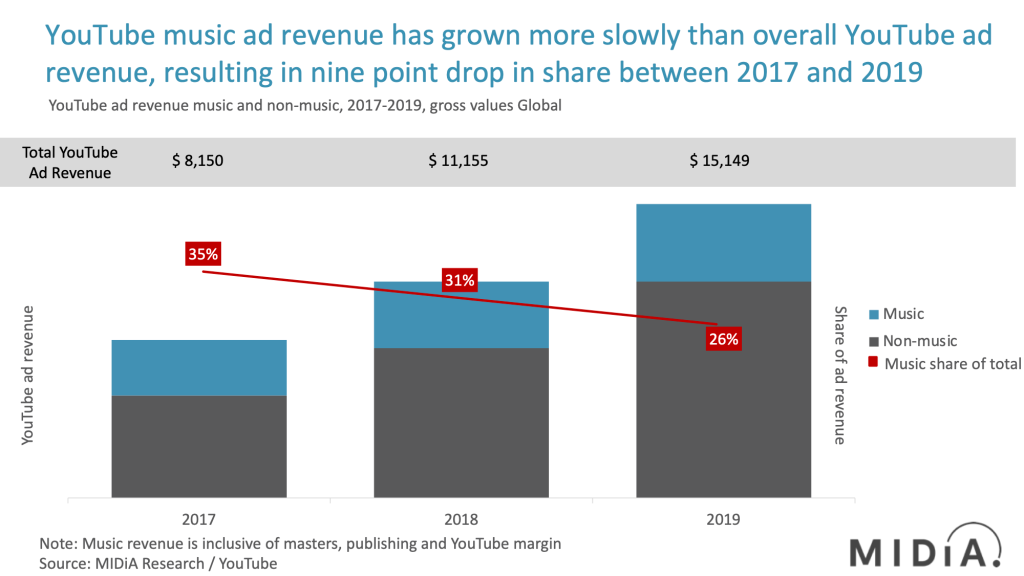

Social music is streaming’s new growth driver, generating around $1.5 billion in 2020 and growing fast in 2021. It represents a natural evolution of social media rather than an evolution of streaming. Audio is just another tool for social expression, along with video, pictures and words. MIDiA has long argued that Western streaming focuses too heavily on monetizing consumption, at the expense of fandom. While social video does not fix the fandom problem, it does cater to some of the key elements of fandom: self-expression, identity and community. Which means that, in some respects, Spotify and the other DSPs only have themselves to blame for having kept fandom out of their propositions. In doing so, they created a vacuum that TikTok and Instagram eagerly filled.

The data in the above chart comes from MIDiA’s latest music consumer survey report which is available now to MIDiA clients and is also available for purchase here.

Rights holder licensing met market demand

Spotify and the other DSPs are the dominant, core component of recorded music and they will remain so for the foreseeable future. But whereas a couple of years ago it looked like they might be the entire story, now music consumption is moving beyond, well, consumption. Finally, we are seeing music becoming an enabler of other experiences. Historically this was restricted to non-scalable, ad hoc sync deals. Now rights holders have established licensing frameworks that are flexible, dynamic and scalable enough to enable a whole new generation of experiences with music either in a central or supporting role.

DSPs occupy one of streaming’s lanes

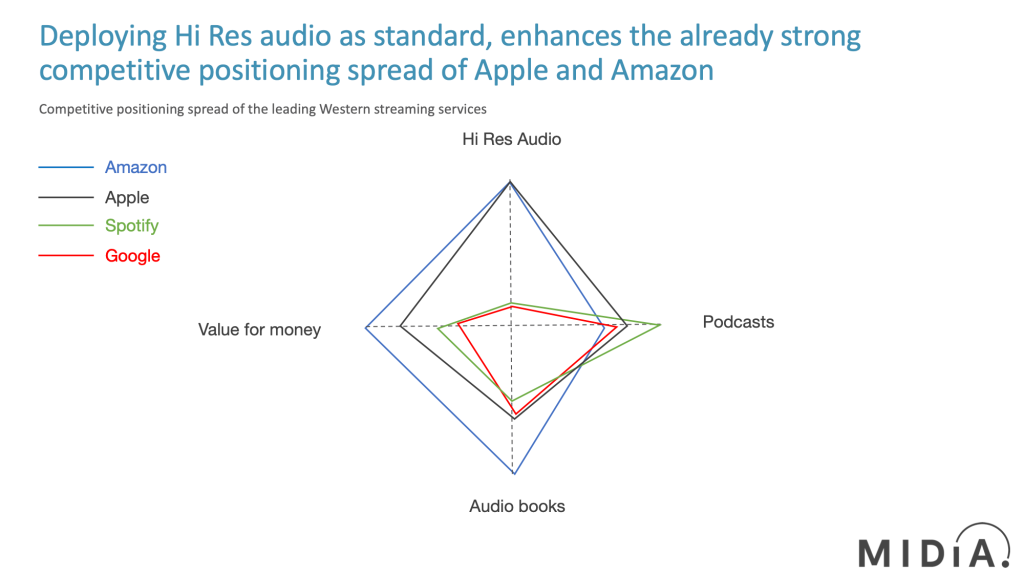

The implication of this is that Spotify and the other DSPs now risk looking like they are stuck in just one lane of the streaming market. What looked like a highway is now just a single lane – and Spotify, Apple and Amazon do not have the assets to build propositions that can get them out of it. Being part of this social music revolution requires both massively social communities and video. They could all build that, of course, but with little guarantee of success. YouTube is a different case, having launched Shorts in a belated bid to ward off TikTok’s audience theft – but at least it is now running that race, and Alphabet reported 15 billion daily global views for Q2.

An increasingly segmented market

Spotify and other DSPs now find themselves not being part of streaming’s new growth story and, YouTube excepted, with no clear path to becoming part of it. To be clear, Spotify will continue to be the world’s largest subscription revenue generator and the DSP subscription model will continue to be the biggest source of revenue, at least for the foreseeable future. But revenue growth will increasingly come from elsewhere. In many respects this simply reflects the maturation of the music streaming market. Consider video streaming. Netflix added just 1.5 million subscribers in Q2 2021 while YouTube grew by 84% and TikTok went from strength to strength. Netflix occupies just one lane in a multifaceted streaming market. The same is now becoming true of the DSPs.

Time to do a Facebook?

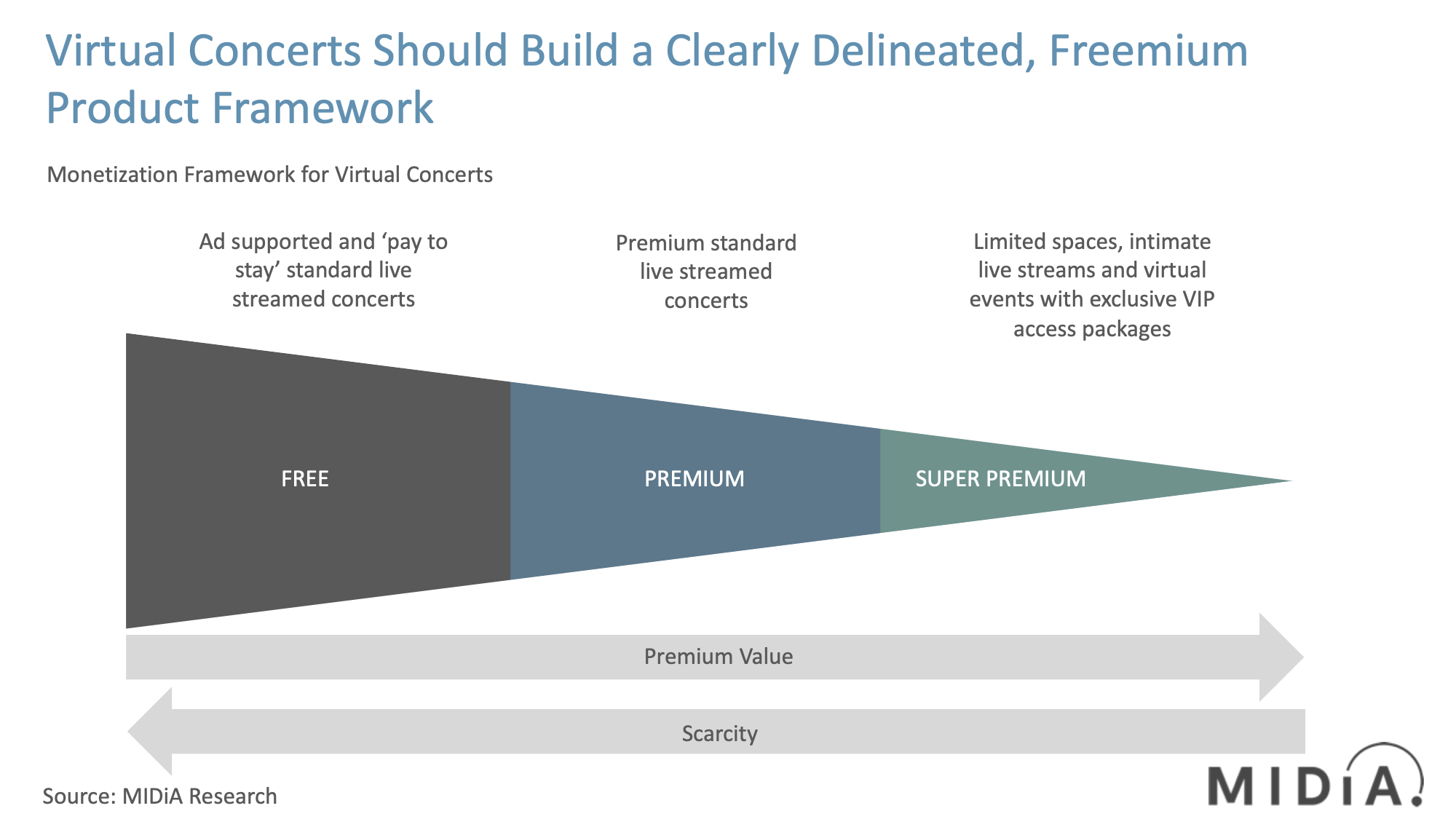

So, what can Spotify and the other DSPs do about it? If Spotify really wants to ‘own’ audio, then it will have to do what Facebook did to ‘own’ social: create a portfolio of standalone sister apps. Facebook would have become the Yahoo of social media if it hadn’t bought / launched Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger. The signs are already there for Spotify. Even ignoring the slowdown in monthly active user (MAU) growth in Q2 2021, podcast users stopped meaningfully growing as a share of overall MAUs in Q4 2020. It turns out that trying to compete with yourself in your own app is hard to do. The time may have come for a standalone podcast / audiobook app (by the way, I’m just taking it as read that Spotify is going to take audiobooks a whole lot more seriously). If Spotify does launch a podcast app, then the case suddenly becomes a lot clearer for other audio-related apps, all of which could include subscription tiers, such as social short video, karaoke, and artist channels.

The more probable outlook however is for specialisation, with segments going deep and vertical rather than wide and horizontal. While Spotify, and other DSPs, might have success in one or more side bets, it will be the specialists who lead in streaming’s other lanes. Whatever the final market mix looks like as a result of this change, the streaming market is going to be more diverse and innovative for it.

MIDiA’s latest subscriber report ‘Recovery Economics: Music, Games, Live Streams and the Future of Concerts’ has just been published and

MIDiA’s latest subscriber report ‘Recovery Economics: Music, Games, Live Streams and the Future of Concerts’ has just been published and

Disney tidies its streaming stats:

Disney tidies its streaming stats: