The UK Parliament’s inquiry on the economics of streaming appears to be building a case for equitable remuneration (ER). There are many iterations of what ER can mean, but a simplified description of what is in play here is: a share of streaming revenue being paid directly by the DSPs to an entity which then distributes directly to artists, thus bypassing the whole ‘do labels pay artists enough’ debate. Though there are some examples of ER in place – such as in Spain – if the UK went down this route it would, in many respects, be setting a global streaming precedent. What is more, it is a solution that would likely have more income impact on artists than alternatives such as user-centric licensing. ER has the potential to transform artist income, but quite probably not the way you think.

Superstar skews even apply to streaming’s superstars

The starting point for ER is the premise that most artists do not make enough money from streaming. It is tempting to look at Spotify’s 43,000 artists that account for 90% of its plays as evidence that the pool of high-earning artists is becoming sizeable. Indeed, the implied average income for these artists was around $100,000 in 2020. But averages can be misleading, especially when there is non-linear distribution.

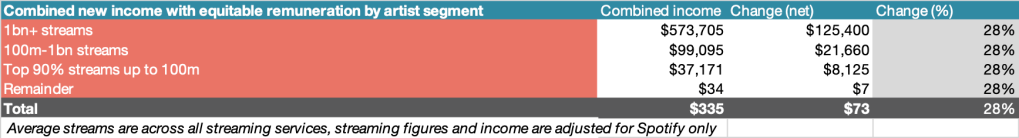

To illustrate the point, we can slice this 43,000 a few ways thanks to a number of industry figures. In his DCMS presentation, WMG’s Tony Harlow stated that the label had eight artists globally that had a billion streams. Assuming that is a ‘lifetime’ rather than annual figure and applying market share assumptions, that gives us around seven artists across all labels generating a billion streams a year. Additionally, the BPI recently reported that 200 artists generated more than 100 million streams each in the UK in 2020. Taking these figures into account, applying assumptions to account for global figures and Spotify market shares and then factoring in per-stream rates and the total number of releasing artists globally, we end up with the following:

98% of Spotify’s 43K club earn a more modest $29,046 a year (after label deductions). Which isn’t bad when you consider that Spotify is just one part of much bigger streaming economy. Against that, though, those artists are just 0.76% of all artists globally – this is very nearly as good as it gets to be as an artist. Only 1,007 do better.

The remaining 99% earn an average of just $26 a year, and that figure includes not just the around five million artists direct, but also independent artists and even major label artists. Also, just as within the superstar segment, distribution is not linear, but the point is hopefully clear.

The added complication in all of this is that not all of the royalties that Spotify pay for the streams of its 43K club actually end up with artists, as many will not be recouped. WMG’s Harlow suggested that a typical major label artist might need to generate a billion streams to be recouped, and there were just seven of those made in 2020 (indeed an artist on a 15% deal would need 1,010,101,010 streams to pay off a $500,000 advance, assuming a headline per-stream rate of $0.0033 for the label). As artists recoup over multiple years, the recouped figure will be far north of seven and may be closer to the 1,000 that generated between 100 million and one billion streams. So, a majority of Spotify’s 43K club may not be earning any royalties at all.

Hence, there is a double case for ER:

- To ensure all artists earn more

- To ensure artists who are not recouped earn at least some royalty income

And so, onto ER…

Again, using Spotify to illustrate, a 5% ER levy on Spotify would be equivalent to around $400 million for 2020, and around $1.1 billion at an industry level (excluding YouTube from the calculations). Not considering recoupment rates and assuming a single artist share of 32.5% (the average of major and indie royalty splits) this would equate to a 28% increase of income for all artists. Certainly, a welcome shift. But, just in the same way that user centric can have the unintended consequence of benefiting bigger artists, it is the superstars who do best, by dint of simple arithmetic.

There is an implied misconception with ER that ‘equitable’ implies some sort of quasi-socialist redistribution of wealth. It does not. Instead, it allocates income with the same distribution skews that make streaming the superstar economy that it is.

The one billion-plus-streams artists would earn an extra $125,400 a year from Spotify (around $350,000 across all services), but further down the ladder the pickings are more meagre. The 98% of Spotify’s 43K club that currently earn $29,046 would get an extra $8,125 (around $21,000 across all services). A meaningful amount, but unless you are a solo act probably not enough to transform streaming into a liveable income source. And don’t forget, we are still talking about the very top echelon of artists here; for the remaining 99% of artists the average additional income from ER would be $7 a year (though again, the distribution would not be linear, so some will earn in the hundreds and some in the low thousands).

An intriguing unintended consequence is that the average major label artist would likely see a higher percentage increase than independent artists. The reason is very simple: around 80% of major label artists are not recouped so they are currently earning zero streaming royalties, which means ER would be a 100% increase. A far smaller share of independent artists have advances so will be in the 28% bracket.

There is no silver bullet solution to artist income

The key takeaway from this exercise is that just as with user centric, ER is not a silver bullet that is going to fix all of the ails of streaming for creators, mainly because there is no silver bullet. The fractional economics of streaming need scale to deliver benefits, which means that rightsholders (i.e. those with large scale catalogues) benefit far more than the majority of artists (i.e. those with small scale catalogues).

None of this is to say efforts like ER should not be pursued – they should. But expectations should be managed for the majority of artists. As Will Page puts it, there are simply too many mouths to feed (i.e. too many artists fighting for ever smaller slices of a finite royalty pot).

And did you miss the glaring omission from this analysis? Songwriters. In fact, if Spotify and co. are compelled to pay 5% ‘off the top’ to artists, then they are going to need to make up that revenue somewhere else, which probably means a combination of royalty dilution through podcasts and audiobooks, reduced rates paid to labels, more direct deals with artist etc. Crucially, with DSP margins pulverised, good luck with publishers squeezing any further increases in rates in the future. Artist ER could inadvertently put a stop to songwriter royalty increases. Such are the ways of unintended consequences.