The whole essence of fandom is being turned upside down. An emerging crop of streaming-native artists is finding its audience in a much more targeted and efficient way than via the traditional music marketing. Instead of blowing a huge budget on carpet bombing TV, radio, print, online artists and their teams are finding their exact audiences, focusing on relevance and engagement rather than reach and scale.

The traditional model is great at creating household brands but so much of that brand impact is wasted on the households or household members that are not interested in the artist. Niche is the new mainstream. Targeted trumps reach. But too many label marketers fear that unless they use the mass media platforms, they will not be able to build national and global scale brands. They might be right, at least in part, but this is how the future will look and new marketing disciplines and objectives are required. Here’s some brand new data to show why.

Since Q4 2016 MIDiA has been tracking leading TV shows every quarter for awareness, fandom, viewing and streaming. Since the start of 2019 we have been doing the same for artists, with viewing swapped out for listening. These metrics provide a rounded picture of an artist’s full brand impact and consumption, while the ratios between these metrics give a unique view of just how individual artists are performing and of the impact of their respective marketing strategies. Later in the year we will be feeding this data into Index for Music,a unique new dashboard tool to combine with data from social platforms, streaming, searches, reviews and other metrics that create an end-to-end view of artist impact. We have already built our Index for Video tool which you can find out more about here.

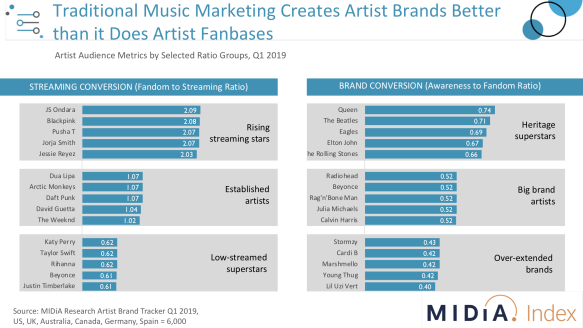

In the above chart, using the consumer data component of Index, we have taken a contiguous sample of the five artists that represent the mid-point of each third of the rankings (i.e. top, middle and bottom) for two of these ratios:

- Fandom-to-streaming, which we call Streaming Conversion

- Awareness-to-fandom, which we call Brand Conversion

The results show some very clear artist clusters with clear implications for artist success and marketing strategy (remember, these are ratios not rankings of how well streamed or popular they are):

Streaming Conversion

- Rising streaming stars: These artists have twice as many people streaming them as they do fans. These artists are largely younger, frontline artists that are building their careers first and foremost on streaming platforms. These are artists that have not yet built their fanbases but are being pushed hard by their labels on streaming and elsewhere. Their listening is being driven by promotional activity. Pusha-T is the exception, a much longer established artist.

- Established artists: These artists are largely well-established artists whose streaming audience penetration correlates with their fanbases. Their listening is largely organic. Dua Lipa is the exception, still relatively early in her career but already with an established fanbase driving organic streaming.

- Low-streamed superstars: These are artists that built their careers in the pre-streaming era and while are household names, have streaming audiences smaller than their fanbases, not having managed to migrate large shares of their audiences to streaming

Brand Conversion

- Heritage superstars: The majority of people who know these big heritage acts like them. In some ways brand conversion is an easier task for such artists than frontline artists. As they have been around so long, it tends to be the very bests of their catalogue that people know. The fact Queen outranks the Beatles is testament to the way in which the biopic Bohemian Rhapsody has created new relevance for the band.

- Big brand artists:This eclectic mix of artists are – Julia Michaels excepted – well established artists that have benefited from years of label marketing support, with about half of all people that know them liking them.

- Over-extended brands: One of the most important changes wrought by streaming and social is that fanbases no longer need to be built via mass media. However, big artists, especially major label ones, still rely upon mass media to become global stars. The result is a lot of wasted marketing budget. In this group, which is dominated by Hip Hop artists, more than half of the people who have been made aware of the artists do not like them. The marketing dollars spent on reaching those people has not converted.

We will be diving much deeper into this data in a forthcoming MIDiA client report and also at our next free-to-attend (depose required) event in central London: Managing Fandom in a Fragmented Content Landscape. Join us at the event to get a sneak peak of MIDiA’s artist data and our Index tool. All attendees will get a free copy of the presentation. In addition to the data key note there is a panel featuring people from Kobalt, TikTok, ATC and more to be confirmed. Sign up now, only limited places remain!

See you there!