If 2014 was the year of fear, uncertainty and doubt for streaming then 2015 is shaping up to be the year in which streaming starts to deliver. In fact so far streaming has helped drive revenue growth in the first half of 2015 for markets as diverse as Italy, Spain and Japan as well as of course in the streaming Nordic heartlands of Sweden, Denmark and Norway. All this despite an accompanying average decline in download revenue of 7%. But as I have long said, there is only so far that 9.99 AYCE (All You Can Eat) subscriptions can go. This value proposition and price point combination constrains appeal to the aficionados and the upper end of the mainstream. Pricing will be key to unlocking new users (as Spotify’s focus on the $1 a month for 3 months promo shows). However some highly influential elements within major labels are more resistant to pricing innovation now than they were this time last year. So don’t hold your breath for the long overdue pricing overhaul. The other side of the 9.99 AYCE equation though is just as important, namely choice, or rather, less choice. In fact, done right, cut down, niche music offerings should be able to fix the pricing conundrum too.

Too Much Content Is No Value At All

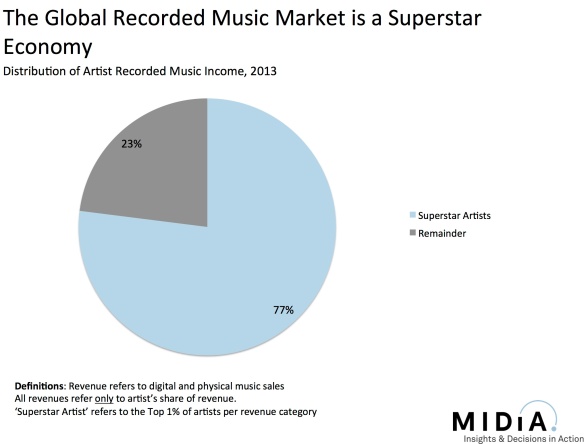

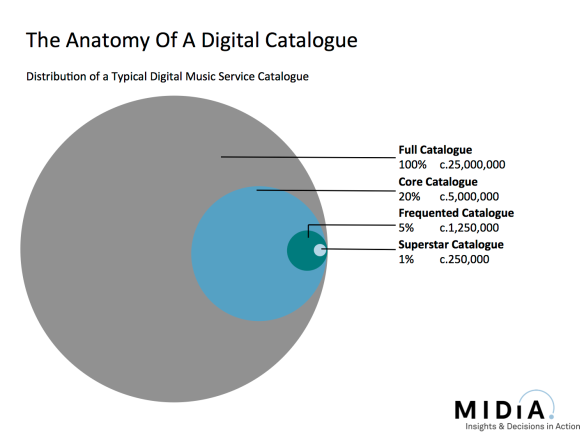

Most people are not interested in all the music in the world and most people are not interested in spending $9.99 (or the local market equivalent) a month for music. All the music in the world is a compelling proposition for super fans, but it is both a daunting prospect and more than is required for casual fans. In fact the supposed benefit becomes a problem, the excess of choice begets the Tyranny Of Choice. Indeed, just 5% of streaming catalogues is regularly frequented. Most of the rest is irrelevant for most consumers.

Cord Nevers Are A Music Industry Problem Too

Most music fans like one or more kinds of music most. While super fans are happy to pay for the ability to get everything, mainstreamers are not. This is exactly the dynamic we are seeing in the video space, with consumers increasingly turning to smaller, cheaper services such as Netflix and Amazon rather than paying through the nose for an excess of cable channels. The TV industry calls these consumers cord cutters (i.e. those that cancelled their TV subscriptions) and cord nevers (i.e. those that never paid for cable). Now the music industry is facing its own cord never challenge: consumers who have never taken up a music subscription and have no intention of doing so. In the past they would have spent some money on downloads, now they’re just watching more music videos YouTube. The music industry quite simply does not have a Netflix for its cord nevers to go to instead of the full priced subscription option.

The Case For Niche Playlist Services

But give those more casual music fans a music app just built around their tastes and for a fraction of the price and the equation changes from zero sum. Imagine genre specific playlist apps for $3 or $4 month. A dozen curated playlists, a handful of featured albums and a couple of radio stations, all just of your favourite style of music and all streamed into a dedicated app. Not only does this proposition deliver clear value, it also gives the industry an opportunity to open up new users that have thus far not been swayed by the broader utility play of AYCE services.

Imagine a Country app, a Classic Rock app, a Hip-Hop app, a Metal app, an EDM app, a Jazz app…. Each of these would create clear appeal within the mainstream elements of genre fan bases. And while there is some risk of cannibalizing $9.99 services, this should be small if they are 100% curated (i.e. no on demand element) because they would be unlikely to appeal to aficionados and the super-mainstream. These niche music apps could be delivered by standalone curated playlist service providers like MusicQubed, white label providers like Medianet and Omnifone, or even by AYCE services like Spotify ‘doing-a-Facebook’ by spinning out standalone apps.

The Marketplace Needs Niche Services Right Now

Niche services are not however a nice-to-have, an optional extra for the industry. They will be crucial to unlocking the scale end of the subscription market and they will be needed sooner rather than later. Organic subscription growth (i.e. not including the temporary adrenaline shot of Spotify’s limited time price promotions) is not growing fast enough. Apple Music looks set to add a significant amount of new users before year-end but many of those will come at the direct expense of the incumbents. All the while YouTube is leaving everyone else for dust: the amount of net new video streams (i.e. free YouTube views) in H1 2015 was more than double that of net new audio streams.

The 9.99 AYCE model still has a lot of life in it yet, but just as the mobile phone market has far more choice than high end devices, so the subscription market desperately needs the diversity that niche services would bring.