I recently keynoted the annual Future Music Forum in Barcelona. These are some highlights of the keynote. If you would like the full slide deck please email me at mark AT midia research DOT COM.

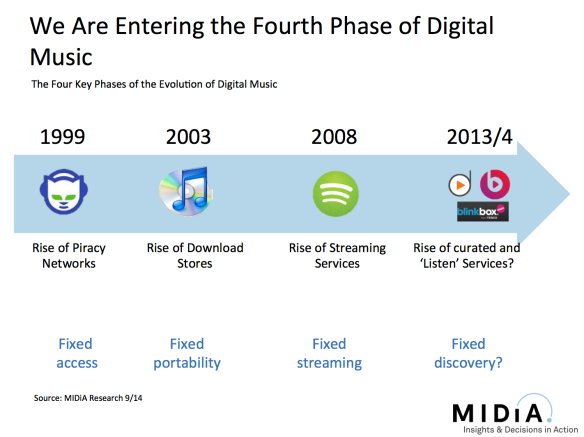

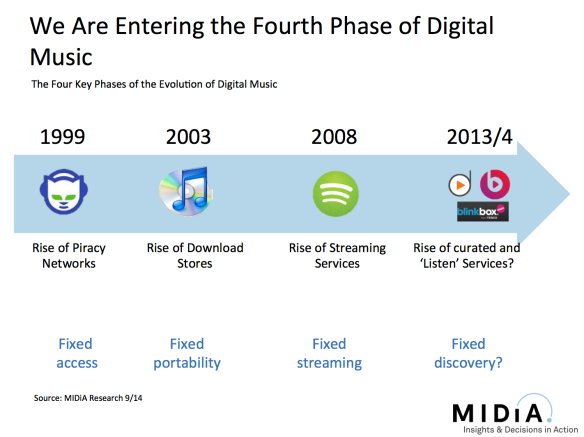

Streaming is turning years of music business accepted wisdom on its head but did not arrive unannounced, it is just one chapter in the evolution of digital music. Each of the four phases of digital music have been shaped by technologies that solved problems. Now we are entering the fourth phase, bringing meaning to the 30 million tracks Spotify et al gave us access to. This might look like a simple honing of the model but it is every bit as important as the previous three stages. 30 million tracks is a meaningless quantity of music. It would take three lifetimes to listen to every track once. There is so much choice that there is effectively no choice at all. This is the Tyranny of Choice.

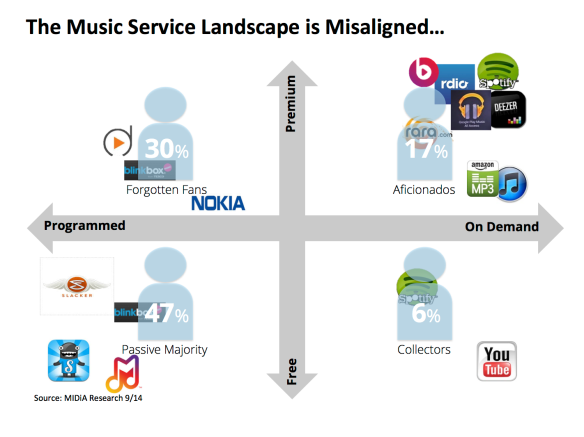

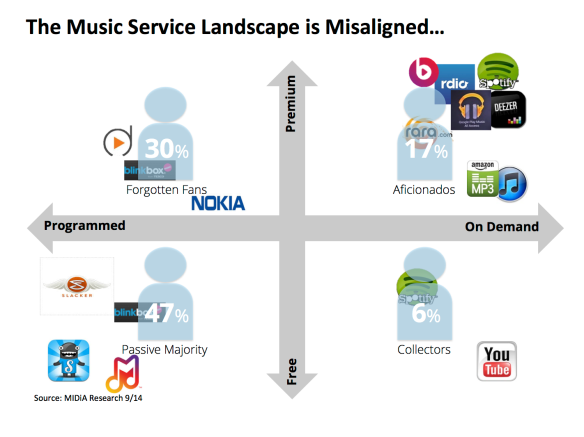

But the for all the evolution, today’s digital music marketplace is an unbalanced one. We have more than 500 music services across the globe but too many of them are chasing after the same customers with weakly differentiated offerings. This wouldn’t matter so much is if the competition was focused on where the consumer scale is, but this is anything but the case. The majority of paid music services are targeting the engaged, high spending Music Aficionados who represent just 17% of all consumers.

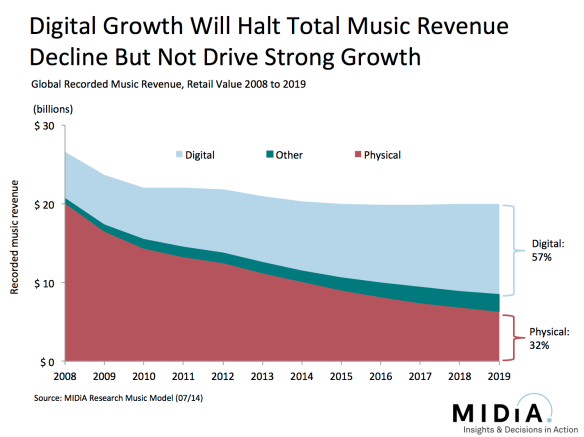

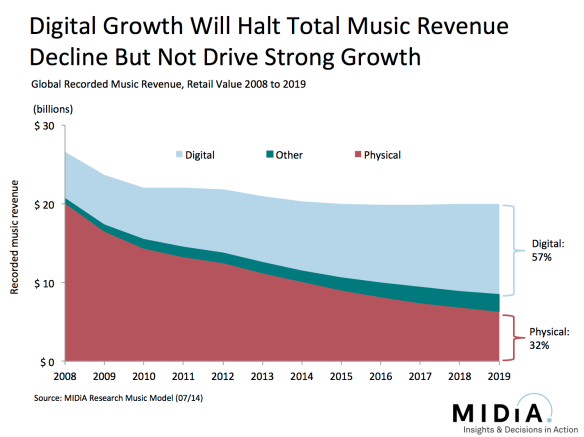

The consequences of the imbalance in digital music strategy are also easy to see in total revenues. The last decade has been one of persistent decline in recorded music revenue and by 2018 the most likely scenario is one of stabilization rather than growth. This is because of a) the CD and b) the download.

No one has taken the demise of the CD seriously enough. It still accounts for more than half of global revenue and more than three quarters of revenue in two of the world’s biggest music markets. Yet far too many CD buyers are being left to simply stop buying entirely because they see no natural entry point into the digital services market. No one appears to be putting up a serious fight for them. Meanwhile the streaming services that have been chasing those same aficionados that Apple engaged are now busy turning that download spending into streaming spending, which ends up being, at best, revenue transition rather than growth. Consequently CDs and downloads will end up declining at almost the same rate over the next five years.

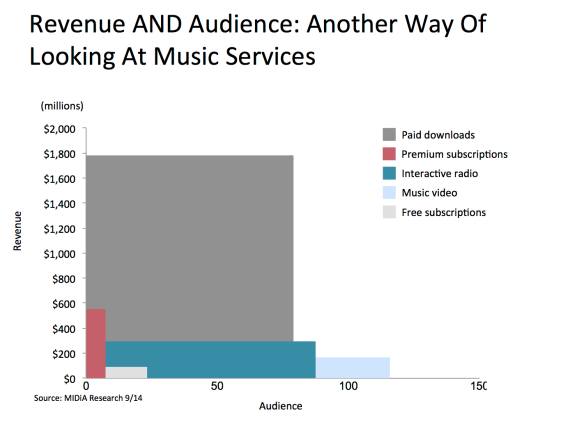

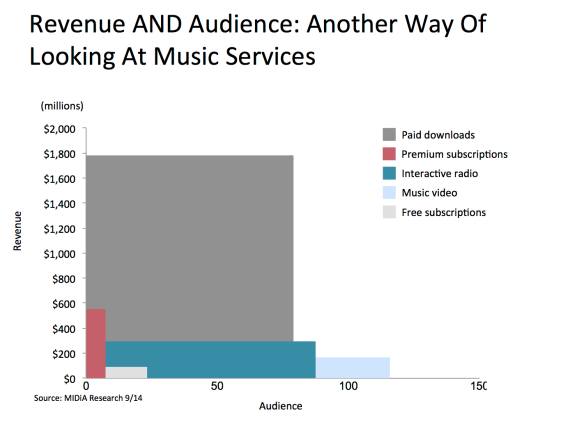

Nonetheless the imbalance remains. Part of the reason we got into this state of affairs is the music industry’s obsession with revenue metrics: chart positions, market share and ARPU. Compare and contrast with the TV industry’s focus on audiences. It is time for the music industry to start thinking in audience terms too.

When we do so we see a very different picture. Here we have the US digital music market plotted by revenue and by audience size. Subscriptions pack a big revenue punch but reach only a tiny segment of the market while YouTube has vast reach but delivers remarkably little in terms of direct revenue. Meanwhile downloads, for all their doomed future, are still by far the best combination of scale and revenue.

The issue of free services stealing the oxygen from paid ones is a perennial one and is effectively a digital rerun of the never-to-be-resolved radio driving or reducing music sales debate. But it has far more impact in digital. With services like YouTube and Pandora the discovery journey is indistinguishable from the consumption destination. When they don’t lead to sales can they really be called discovery anymore?

Free is of course the language of the web. The contagion of free is legion. And free is where the audience growth is. This is the circle the music industry must square.

For 15+ years the music industry has been running to catch up, never quite able to get ahead of the game, an unavoidable feature of the process of digital disruption. But although the consumer behaviour shift is inevitable the future direction of the music business is not and it will be shaped most by three key factors:

- The continued evolution of consumer behaviour

- Technology company strategy

- Income distribution

Consumer behaviour. The most important consumer behaviour trends are not the steady transition of the Aficionados or even the Forgotten Fans but of the next generation of music consumers, the Digital Natives. Free and mobile are the two defining elements of their music behaviour. Of course younger people always have less disposable income, but there is a very real chance that we are beginning to see demographic trends locking in as cohort trends that will stay with these consumers as they age. For a generation weaned on free, the more free you give them, the more they will crave it. Whatever course is plotted, success will depend upon deeply understanding the needs of Digital Natives and not simply trying to shoe horn them into the products we have now that are built for the older transition generation.

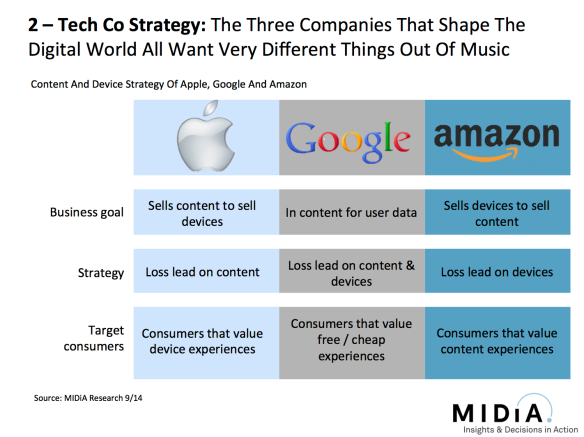

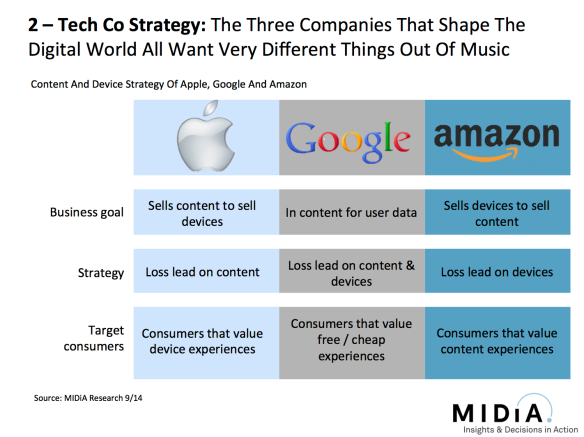

Technology companies: Apple, Amazon and Google each in their own ways dominate digital music. But most importantly they all want very different things from it. For each of them music is a means to an end. All are willing to some degree to loss lead on music to achieve ulterior business objectives. All of which is great for labels and publishers as they get their royalties, advances and equity stakes. But for the pure play start up it means competing on an uneven footing with giant companies who don’t even need music to generate a revenue return for them.

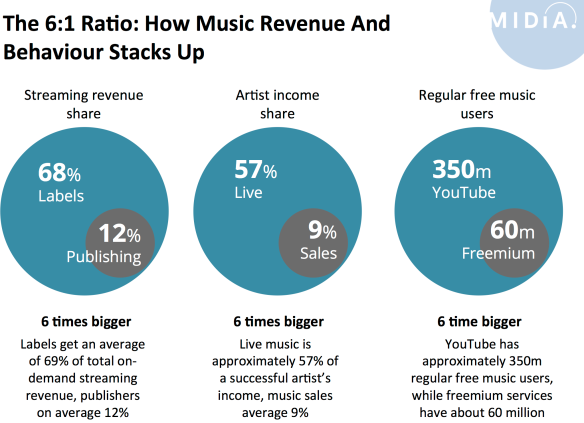

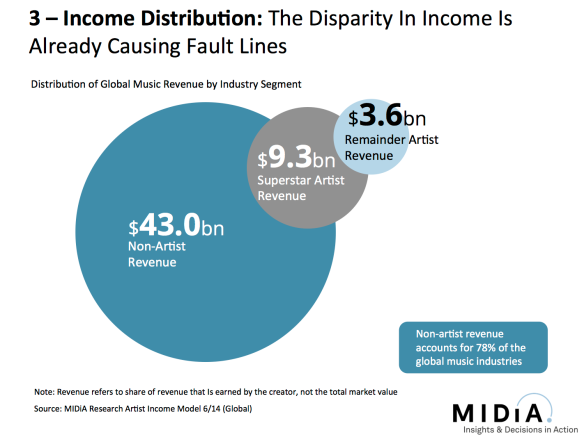

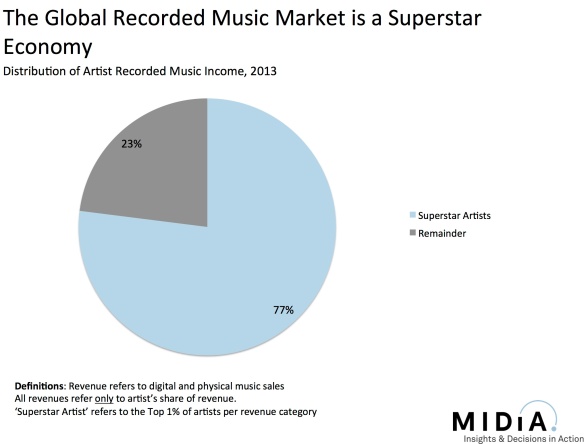

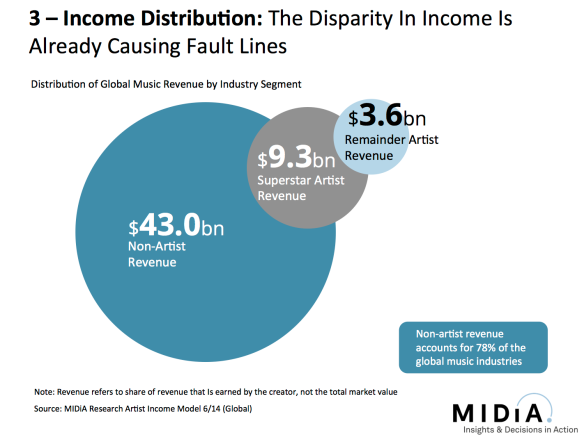

Revenue distribution: Artists and songwriters found their voices in recent years. Partly because of the rise in social media but also because so many are now paying much more attention to the business side of their careers. The fact they are watching download dollars being replaced by streaming cents only intensifies matters, as does the fact that the top 1% of creators get a disproportionately large share of revenue. It has always been thus but the signs are that the disparity is becoming even more pronounced in the streaming age, with the effects felt all the more keenly because unless you have vast scale streaming can too easily look like chicken feed to an artist compared to download income.

But artist and songwriter discontent alone is not going to change the world. Their voices are just not powerful enough, nor do most fans care enough. Also labels and publishers remain the most viable route to market for most artists. Matters aren’t helped by the fact that artists who demand an audit of their accounts to work out where their streaming revenue has gone swiftly accept their label’s hefty silence payment and the accompanying NDA. Artist discontent while not decisive in impact is beginning to apply important pressure to the supply end of the music business.

So those are the three big challenges, now here are three sets of solutions. And I should warn you in advance that I am going to use the P word. Yes, ‘Product’.

I get why product sounds like an ugly word. It’s a term you use for baked beans, for fridges for phones. Not a cultural creation like music right? True enough, when we’re talking about the song itself, or the performance of it, product is irrelevant. But as soon as we’re talking about trying to make money out of it as a CD, download, stream or however, then we’re firmly in the territory of product. It is both naïve and archaic to think otherwise. When artists got megabucks advances and never had to worry about the sustainability of their careers and everything revolved around the simplicity of CD sales you could perhaps be forgiven for turning a blind eye. But now there is no excuse.

So with that little diatribe out of the way, on to the first solution.

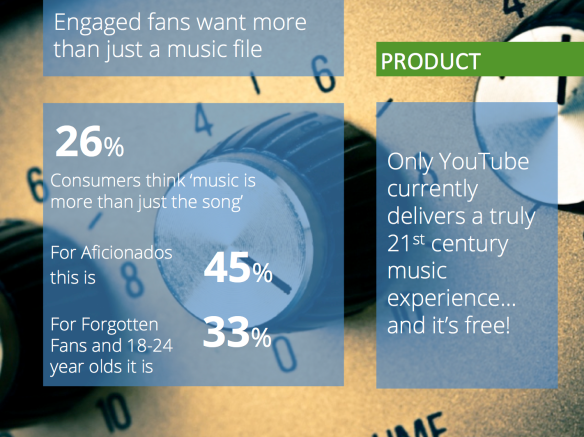

Music product: The harsh reality is that music as a product has hardly evolved in the digital realm. A lot has been done around retailer and business model innovation, but the underlying product is the same static audio file that we found in the CD. Meanwhile the devices we are spending every growing shares of our media consumption have high definition touch screens, graphics accelerators, accelerometers…audio hardly scratches the surface of what tablets and smartphones do.

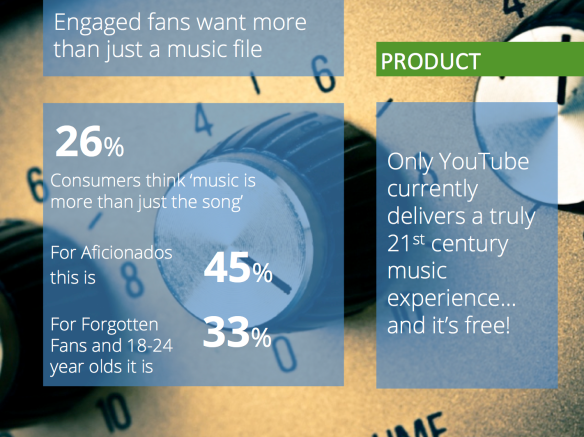

Music is always going to be about the song, but it is also about the artist and their story. That’s what a quarter of consumers think, and 45% of aficionados and a third of digital natives. Video, lyrics, photos, reviews, interviews, acoustic sets, art, these are all ways in which the artist can tell their story and they all need to be part of the product. Most of this stuff is already created by labels, artists and managers but it is labelled marketing. Putting this together into a curated, context aware whole is what will constitute a 21st century music product.

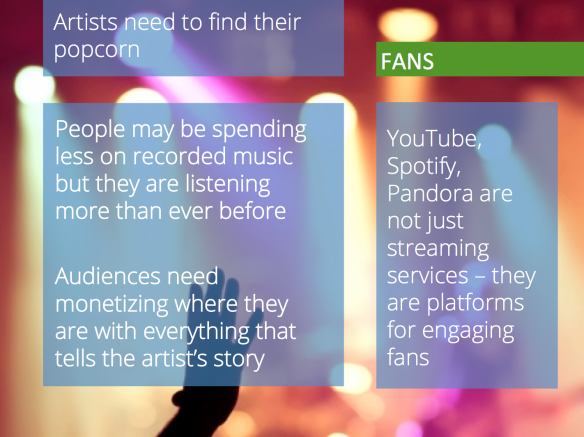

Fans: Artists and fans are closer than ever but this journey is only getting going and artists need to get smarter about how to monetize their fan bases. Artists need to find their popcorn. What do I mean by this? Well when the cinema industry started out it was a loss making business. To try to fix this cinemas started by experimenting with the product, putting on double bills but that wasn’t enough. Then came innovation in the format by adding sound. Then the experience itself by co-opting the new technology of air conditioning from the meat packing industry. Still no profit. Finally cinemas found the solution: popcorn. With a 97% operating margin, popcorn along with soda and sweets quickly became how cinemas become profitable entities. Artists need to find their popcorn. To find out what other value they can deliver their fans to subsidize releasing music. It’s what newspapers are doing with wine clubs and travel clubs, and in some instances even with Spotify bundles!

Labels: Finally we have agencies or what you might call labels, but I’m going to call them agencies, because that is what they need to become. The label model is already going under dramatic transformation with the advent of label services companies like Kobalt and Essential and of fan funding platforms like Pledge and Kick Starter. All of these are parts of the story of the 21st century label, where the relationship between label and artist is progressively transformed from contracted employee to that of an agency-client model. Labels that follow this model will be the success stories. And these labels will also have to stop thinking within the old world constraints of what constitutes the work of a label versus a publisher versus a creative agency versus a dev company. In the multimedia digital era a 21st century labels needs to do all of this and be able to work in partnership with the creator to exploit all those rights by having them together under one roof.

And finally, the grand unifying concept to pull all this together: experience. Experience is the product. The internet did away with content scarcity. Now the challenge that must be met is to create scarce, sought after experiences that give people reasons to spend money on the artists and music they love.