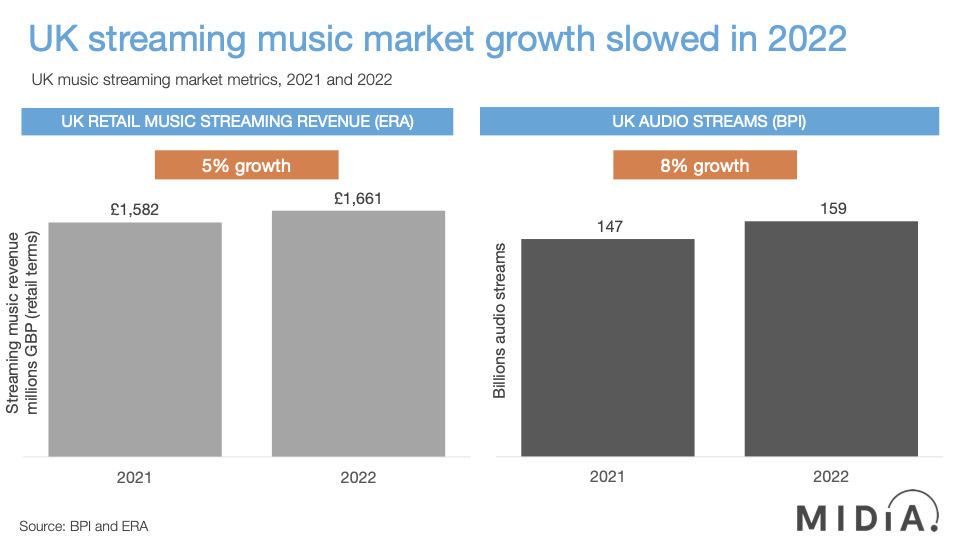

ERA, The UK trade association for entertainment retailers released its annual estimates for the UK entertainment market, showing strong growth for video but less impressive increases for music and games. The streaming slowdown has been on the cards for some time now and there is an argument that the strong growth recorded in 2021 was boosted by the combination of the global economy’s catch-up process that year, following the pandemic-depressed 2020 and the extra impetus delivered by upfront payments for non-DSP streaming. By Q3 2022, global label streaming revenues were up by 7%, compared to 31% for the same period one year earlier. Now ERA estimates* that UK retail streaming revenues were up by just 5%. Meanwhile, the BPI – whose numbers are based on actual market data – reported total audio streams were up by 8% in the UK. A clear streaming market trend is beginning to emerge.

There are no two ways about it, 2023 is going to be a challenging year. The sheer volume of disruptive trends is unprecedented in modern times, and this comes at the exact same time that the Western music streaming market is beginning to slow. A perfect storm. But slowdown does not need to mean decline, at least not for subscriptions. MIDiA’s data shows that consumers are going to cut down on going out and on real live events before cancelling subscriptions, and because they will be going out less, they will need more to keep them occupied at home. So, streaming subscriptions (music, video, and games) may prove to be the affordable luxuries that keep consumers entertained throughout the coming year. Holding onto subscribers should, therefore, be an achievable goal – adding large numbers of new subscribers, though, may be a step too far, particularly in markets most impacted by the economic headwinds. Emerging markets might be a different story.

Ad supported though, is a different story. If overall consumer spending softens, then so too will ad spend. With ad revenues representing 27% of all streaming revenues, a significant drop in ad revenue in 2023 (e.g., -8%) could, in a bear-case scenario, be enough to slow overall global streaming revenue growth almost to a halt. Non-DSP was a major driver of industry growth in 2020 and 2021, but as most of it is ad supported, this segment is far more vulnerable to economic pressures than subscriptions. Non-DSP is a segment for periods of plenty, perhaps less so for times of scarcity.

If the global streaming market finishes 2022 with the 7% growth that it is currently tracking to be, it will be entirely in line with the bear-case scenario that MIDiA published last year. We would much rather have had it tracked to our growth-case rate of 27% but, unfortunately, this looks like it may be one of those situations where MIDiA’s glass-half-empty view proved to be on the money.

The next few months will provide a much clearer picture, with the big labels, publishers and DSPs reporting their full year figures. Until then, consider this the first note of caution.

For more insight on what 2023 may hold, join the MIDiA analyst team for our free-to-attend 2023 predictions webinar on Wednesday 11th January.

* ERA did a major restatement of its 2021 figures – upscaling them by a fifth from the £1.3 billion that it reported in 2021 to £1.6 billion, having changed the underlying assumptions for its estimates.