When we first formed MIDiA eight years ago, we saw the new entertainment world was going to require a new joined up approach for entertainment businesses. With the start of the ascent of the smartphone we made an intellectual bet that everything was going to become more interconnected, inter-dependent and inter-competitive. Our vision then, was to build analysis and data that cut across siloes, to help previously unrelated industries understand they were becoming connected. The ‘connecting the dots’ tagline that we launched with in 2014 was right for the time, but now the world has moved on. The dots are now connected. That job is done. Now it is time to decide what to do with those connections.

In more recent years we identified new drivers of the entertainment economy, such as:

- Fragmented Fandom

- The Attention Economy

- The Attention Recession

- Creator independence

- Rise of creator tools

- Reaggregation

When we introduced those concepts they took some time to land, but now are increasingly widely accepted as industry currency. Even other research companies have started following our lead, with webinars and research on the attention economy, the attention recession and fandom fragmentation.

But although those trends will continue to play crucial roles, it is an entirely new set of market dynamics that will shape the future as the world enters a period of uncertainty and disruption unprecedented in modern times:

- Attention inflation: As consumers return to pre-pandemic behaviours, they are trying to squeeze all their new-found entertainment behaviours into less available time. Multitasking is rocketing which means each entertainment minute is less valuable as it is increasingly being done alongside something else. Many more consumption hours than actual hours results in attention inflation.

- The splintering of culture: Water cooler moments may not yet be dead but they are fading. Hits are getting smaller (just ask Beyonce) and audiences are fragmenting. But cultural relevance can actually increase within these fragmented fanbases (again, just ask Beyonce). Culture is splintering but may end up more vibrant as a result.

- Scenes and identity: Underpinning and resulting from culture splintering is the rise of scenes, especially micro scenes which populate platforms like Twitter. Scenes are more than just groups of fans, they a cultural movements that that people look to for identity and belonging. Fandom is merely a subcomponent.

- Lean through: Consumers used to just, well, consume. Now though, every more of them want to participate. The line between creation and consumption is blurring. Leaning forward is no longer enough, now audiences want to lean in and create.

- The creator economy: Perhaps the single biggest shift in entertainment in recent years is the rise and rise of the creator economy, straddling virtually every entertainment format. The creator economy is so much more than vloggers and influencers. It represents a reshaping of culture, remuneration and audiences. As such it will reshape entertainment forever.

- Post-peak growth: With inflation soaring and a recession looming, consumers will have less money to spend on entertainment and leisure. Some sectors will suffer, some will sustain but others will grow. Whether it is to survive or to thrive, entertainment companies will need to reshape both their strategies and purpose.

- Rediscovery is the future of discovery: The first phase of streaming was all about discovery. Now, with a surplus of supply and demand constrained by the attention recession, what consumers want as much as what is new, is to re-find what they already know and love.

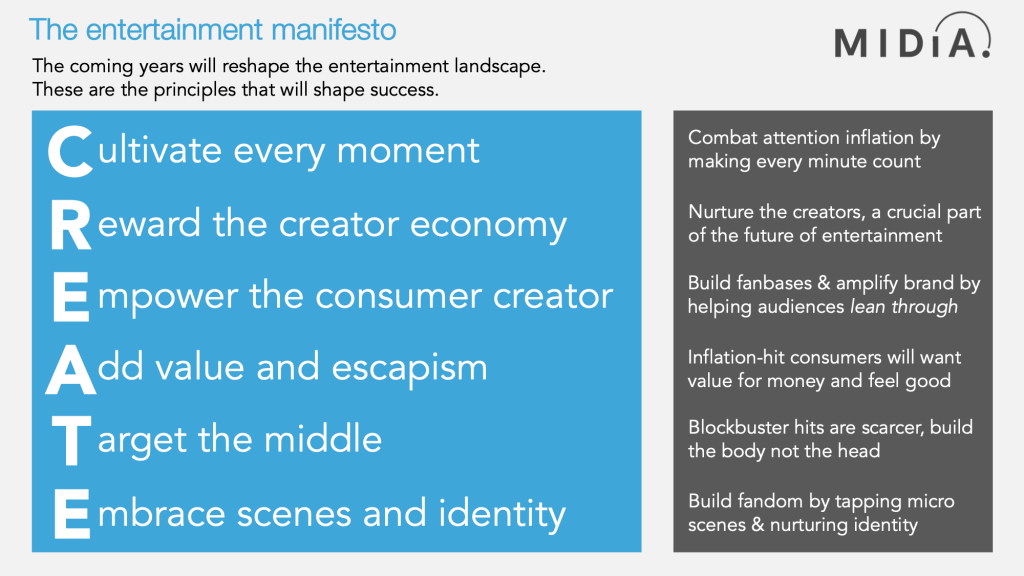

Business as usual is gone. The next chapter of the business of entertainment will require a completely new approach. This is MIDiA’s C.R.E.A.T.E. Entertainment Manifesto for what is required of entertainment companies in this brave new world.

- Cultivate every moment: Multitasking means consumption minutes are losing value. Every moment needs to be made as valuable and as entertaining as it possibly can be. Entertainment companies need their audiences notice what they consume.

- Reward the creator economy: Streaming and social platforms are increasingly dependent on the long tail. The scale economics work for platforms by summing up a multiplicity of niches but they do not work for long tail creators. Platforms and rightsholders need to nurture not just harvest the creator economy.

- Empower the consumer as a creator: Lean through consumers are also super fans. More platforms and services need to give consumers the sort of participation tools that TikTok built is success upon. Not just because it is what audiences want but because it also builds fandom and amplifies entertainment brands.

- Add value and escapism: As consumers’ wallets tighten, subscriptions and ad spend are both at risk. But this need not be an entertainment Armageddon. Instead, entertainment companies should offer consumers what they want: 1) value for money, 2) escape from the harsh realities of daily life.

- Target the middle: While it is tempting to always chase the big hit, the reality is that hits are getting smaller. Success in these coming years will be most easily found by cultivating a collection of mid-sized hits rather than placing all bets on mega hits.

- Embrace scenes and identity: Scenes and identity are the undervalued super power of entertainment. Music, games, sports, creators, books, movies, TV shows – they all move people and they all help define who we are. Truly understanding and harnessing identity will be the difference between survive and thrive.

We hope that the C.R.E.A.T.E. framework and our new Critical Developments coverage help companies and creators plot their paths through the troubled waters ahead. But even more important, is to develop a sense of purpose, a definition of why you do what you do, and to communicate that to your audiences and partners. The entertainment industries have