The Tencent Music Entertainment (TME) F1 filingmakes for highly interesting reading, but don’t expect copious amounts of data to give you an inside track in the way that Spotify’s F1 filing did. Instead TME’s F1 bears much closer resemblance to iQyi’s F1, namely a basic level of KPIs, lots of market narrative and even more space assigned to explaining all of the risks associated with investing in a Chinese company. But, perhaps the most significant thing of all is that TME isn’t really a music company or investment opportunity, but is instead a series of social entertainment platforms, of which music – and much of it not even streaming music – is one minor part.

Risk factors – there’s a lot of them

As with iQiYi’s F1 filing, a lot of the document is taken up with outlining the risks associated with investing in a Chinese company, particularly with regard to the various ways in which the Chinese government can potentially put the business out of existence. Evidence of just how real this threat is for Tencent is very close to home. The Chinese authorities are currently refusing to authorise any new Tencent games – and have not done so since March, while it brings in new restrictions on game playing for kids.Tencent’s shares tumbled as a result. The problem for Chinese companies providing due diligence for overseas investors is that they have to admit that they might not be compliant with all Chinese laws. With the PRC (People’s Republic of China) government not having democratic checks and balances, Chinese companies have to face the real possibility of unpredictable, unchallengeable, draconian intervention, such as is happening with games.

Two particular areas of potential difficulty that the TME F1 highlights are social currency and overseas interests:

- TME makes much of its money from social gifting and virtual items. TME argues this does not constitute virtual currency, so should not be subject to tight PRC regulations. The PRC government may disagree.

- TME is registered in the Cayman Islands and does not actually own many of its Chinese streaming services but instead has shareholdings in, and contractual relationships with, them. This is a risk-laden approach at the best of times, but is given extra spice by the fact the PRC could determine TME to be a foreign interest, which would put it in breach of a whole bunch of PRC regulations.

Other notable risk factors are:

- UGC:TME explains: “Under PRC laws and regulations, online service providers, which provide storage space for users to upload works or links to other services or content, may be held liable for copyright infringement”. It goes on to say: “Due to the massive amount of content displayed on our platform, we may not always be able to promptly identify the content that is illegal.” There are two potential outcomes: 1) things carry on as they are 2) rights holders get itchy feet and TME needs to find someone to help it monitor and police copyright infringement.

- ADS: TME is not offering shares for sale but instead American Depositary Shares (ADS), which in heavily simplified terms means that investors’ money is deposited in US banks in USD and then can in principle be converted into RMB shares at the prevailing currency exchange rate, which may be higher or lower than when the ADS was purchased.

What’s in a number?

Prior to this filing, Tencent had only released one audited music subscriber number – back in Q1 2016 it announced 4.3 million QQ Music subscribers. After that came a succession of press cited numbers that got a lot bigger, but nothing audited. Finally we have a whole collection of numbers to play around with (though see the PS at the end of this post for a health warning on interpreting Chinese company numbers reported in SEC documents).

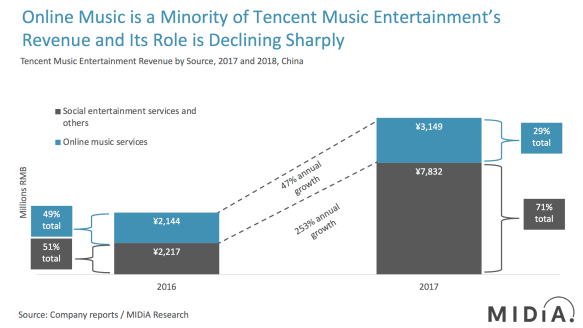

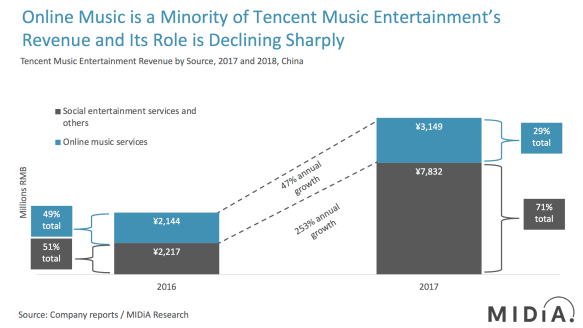

In 2016, TME was very much a music company, with music accounting for nearly half of its RMB 4.4 billion revenues. But by 2017 that picture had changed…and some…with just 29% of its revenues classified as ‘online music services’. Online music revenues grew by 47%, which is impressive enough in isolation, but is much slower growth than the rest of the Chinese paid content market. Video, which parent company Tencent is a key player in, is a major growth area. One sub strand of this is social video, where TME is also market heavyweight. Luckily for TME, it has eggs in many baskets. Social video, which largely comprises live streaming in China, contributed to TME’s social entertainment services revenue growing by 253% (i.e. five times more quickly than online music) in 2017 to reach RMB 7.8 billion – 71% of TME’s total RMB 10.9 billion.

This revenue was driven in large part by live streaming services Kugou Live and Kuwo Liveand by social karaoke app Quanmin K Ge, known as WeSing in the west. WeSing is arguably the biggest ‘music’ app many people don’t know about. Music doesn’t play the same cultural role in China as it does in western markets, thanks in part to the legacy of the oxymoronically named Cultural Revolution, which limits the potential opportunity for music services in China. Karaoke, however, is huge, and WeSing does a fantastic job of converting this demand. By putting social centre stage, TME is able to monetise social in a way that would make Facebook green with envy. As TME explains:

“We provide to our users certain subscription packages, which entitle paying subscribers a fixed amount of non-accumulating downloads per month and unlimited “ad-free” streaming of our full music content offerings with certain privilege features on our music platforms.

We sell virtual gifts to users on our online karaoke and live streaming platforms. The virtual gifts are sold to users at different specified prices as pre-determined by us.”

Putting social centre stage

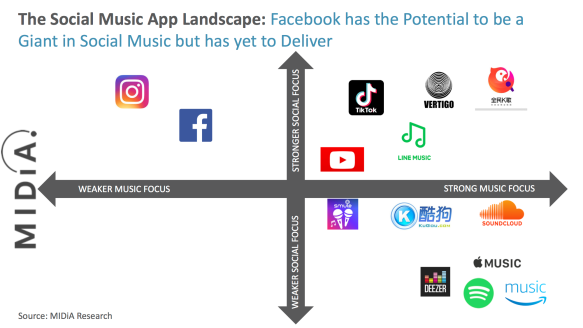

But TME’s social skills are not limited to WeSing. Social seeps from virtually every pore of its music services, with features such as likes, comments, shares, ability to create and share lyrics posters from a song, ability to sing along to songs, see local trending tracks, get VIP packages etc. TME has worked out how to bake true social behaviour into the centre of its music services in a way few western companies have (YouTube and Soundcloud are rare exceptions). Both Soundcloud and YouTube built their services without having to play by the record label rule book. Read into that what you will.

The social power of TME’s end-to-end social music offering is illustrated by this case study:

Ada Zhuang ( ). Ada started out as a talented singer on our live streaming platform. A few months later, she released her debut album on Kugou Music. Since then, Ada has released over 200 songs that have won numerous music awards. Her popularity continued to grow through concerts held across China. A single released by Ada in October 2015 has since then been played over three billon times on our platform.

Through its acquisition of competitor services Kugo and Kuwou, TME has built a music empire, giving it a 76% music subscriber market share and leaving two key competitors: Apple Music and NetEase Cloud Music. TME pointedly makes no reference to Apple Music, despite it having 2.6 million Chinese subscribers in 2017. NetEase, however, does get a name check.

TME reported its combined (net) mobile music MAUs to be 644 million in Q2 2018, though defining its users as unique devices rather than unique users. (Interestingly, it defines its social users on an individual basis.). What is clear is that TME’s music users and social users are mirror opposites in user tally and the revenue they generate; social users are just 26% of users but account for 71% of revenues. Clearly, TME has identified there is a lot more money to be made from social experiences than streaming music. Few western companies saw this opportunity. Musical.ly, founded by Alex Zhu and Luyu Yang, did, and was predictably bought for $1 billion by Chinese company Bytedance, home to Douyin (known as TikTok in the west).

TME’s ARPU numbers hammer home the scale of success for its social segment versus its music side. In Q2 2018 TME was earning RMB 122 a month from social users, against a paid user base of 9.5 million, while its paid music base of 23.3 million was generating an ARPU of just RMB 9.

Interestingly, international expansion is not mentioned once in the 198,984 words of the TME F1 filing. TME explains exactly how it intends to spend the money from the IPO but international is not spelt out. Our bet though, is that TME is playing its cards close to its chest and will indeed go west.

Wildcard

TME is one of a number of Chinese tech firms listing a portion of their stock on US exchanges. Should the US economy topple into a downward trend at some stage, for example as a resulting of an escalating trade war with China, then stocks like TME could give US investors a seamless way of transferring their holdings out of US companies into Chinese ones, without having to change their portfolio mix (ie one tech stock for another) and without having to change jurisdiction. And with China sitting on $3 trillion of foreign currency reserves – with USD the largest part – China could even hasten things along by flooding US currency into the markets, triggering a tumbling exchange rate.

PS

There is an international jurisdictional loophole between the SEC in the US and the CSRC in China. Which in overly simplified terms means that Chinese companies can falsely report numbers in SEC filings,withtheSEC unable to prosecute Chinese miscreant companies and the CSRC unable to take action over the SEC filing.This has resulted in a significant number of fraudulent filings by Chinese companies reverse listing onto US exchanges via dormant US companies, with SEC filings showing numbers up to 10 times higher than their CSRC filings. The only watertight way to validate Chinese company SEC filed numbers, is to corroborate them with CSRC filings. Unfortunately, TME is not a separate entity in China so has not filed any numbers, and, as stated above, Tencent has rarely reported any numbers for its music division. This does not mean that TME’s should not inherently be taken at face value, but it does suggest extra scrutiny might be wise.