Today I have published the latest Music Industry Blog report: ‘The Music Format Bill Of Rights: A Manifesto for the Next Generation of Music Products’. The report is currently available free of charge to Music Industry Blog subscribers. To subscribe to this blog and to receive a copy of the report simply add your email address to the ‘EMAIL SUBSCRIPTION’ box to left.

Here are a few highlights of the report:

Synopsis

The music industry is in dire need of a genuine successor to the CD, and the download is not it. The current debates over access versus ownership and of streaming services hurting download sales ring true because a stream is a decent like-for-like replacement for a download. The premium product needs to be much more than a mere download. It needs dramatically reinventing for the digital age, built around four fundamental and inalienable principles of being Dynamic, Interactive, Social and Curated (D.I.S.C.). This is nothing less than an entire new music format that will enable the next generation of music products. Products that will be radically different from their predecessors and that will crucially be artist-specific, not store or service specific. Rights owners will have to overcome some major licensing and commercial issues, but the stakes are high enough to warrant the effort. At risk is the entire future of premium music products.

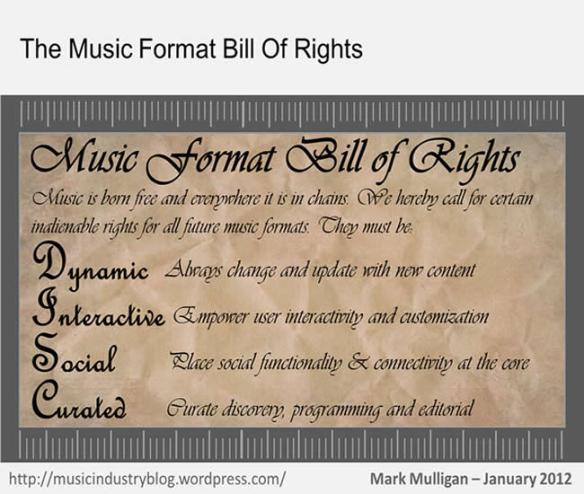

D.I.S.C.: The Music Format Bill Of Rights

The opportunity for the next generation of music format is of the highest order but to fulfil that potential , lessons from the current digital music market must be learned and acted upon to ensure mistakes are not repeated. The next generation of music format needs to be dictated by the objective of meeting consumer needs, not rights owner business affairs teams’ T&Cs. It must be defined by consumer experiences not by business models. This next generation of music format will in fact both increase rights owner revenue (at an unprecedented rate in the digital arena) and will fuel profitable businesses. But to do so effectively, ‘the cart’ of commercial terms, rights complexities and stakeholder concerns must follow the ‘horse’ of user experience, not lead it. This coming wave of music format must also be grounded in a number of fundamental and inalienable principles. And so, with no further ado, welcome to the Music Format Bill of Rights (see figure):

- Dynamic. In the physical era music formats had to be static, it was an inherent characteristic of the model. But in the digital age in which consumers are perpetually online across a plethora of connected devices there is no such excuse for music format stasis. The next generation of music format must leverage connectivity to the full, to ensure that relevant new content is dynamically pushed to the consumer, to make the product a living, breathing entity rather than the music experience dead-end that the download currently represents.

- Interactive. Similarly the uni-directional nature of physical music formats and radio was an unavoidable by-product of the broadcast and physical retail paradigms. Consumers consumed. In the digital age they participate too. Not only that, they make content experiences richer because of that participation, whether that be by helping drive recommendations and discovery or by creating cool mash-ups. Music products must place interactivity at their core, empowering the user to fully customize their experience. We are in the age of Media Mass Customization, the lean-back paradigm of the analogue era has been superseded by the lean-forward mode of the digital age. If music formats don’t embrace this basic principle they will find that no one embraces them.

- Social. Music has always been social, from the Neolithic campfire to the mixtape. In the digital context music becomes massively social. Spotify and Facebook’s partnering builds on the important foundations laid by the likes of Last.FM and MySpace. Music services are learning to integrate social functionality, music products must have it in their core DNA.

- Curated. One of the costs of the digital age is clutter and confusion: there is so much choice that there is effectively no choice at all. Consumers need guiding through the bewildering array of content, services and features. High quality, convenient, curated and context aware experiences will be the secret sauce of the next generation of music formats. These quasi-ethereal elements provide the unique value that will differentiate paid from free, premium from ad supported, legal from illegal. Digital piracy means that all content is available somewhere for free. That fight is lost, we are inarguably in the post-content scarcity age. But a music product that creates a uniquely programmed sequence of content, in a uniquely constructed framework of events and contexts will create a uniquely valuable experience that cannot be replicated simply by putting together the free pieces from illegal sources. The sum will be much greater than its parts.

Table of Contents for the full 20 page report:

Setting The Scene

- Digital’s Failure To Drive a Format Replacement Cycle

Analysis

- Setting the Scene

- (Apparently) The Revolution Will Not Be Digitized

- The Music Consumption Landscape is Dangerously Out of Balance

- Tapping the Ownership Opportunity

- The Music Format Bill Of Rights

- Applying the Laws of Ecosystems to Music Formats

- Building the Future of Premium Music Products

- D.I.S.C. Products Will Be the Top Tier of Mainstream Music Products

- The Importance of a Multi-Channel Retail Strategy

- Learning Lessons from the Past and Present

- We Are In the Per-Person Age, Not the Per-Device Age

Next Steps

Conclusion