Today UK headquartered supermarket chain Tesco announced the acquisition of a 91% stake in UK streaming music service We7. It hasn’t been the easiest of journeys for We7, with the plucky English start-up simultaneously fighting off incursions onto its home turf from the Nordics (Spotify) and the French (Deezer). Which is an uncanny rerun of the last English King Harold I’s annus horibilis 1066 when he fought off the Vikings and before finally losing to the France based (though Viking origin) Normans at the Battle of Hastings. But whereas Harold ended up with an arrow in his eye this isn’t the end of the story for We7.

Tesco might at first sight seem something of an unusual bedfellow for We7, but Tesco has very big digital content aspirations. The We7 purchase follows the acquisition of streaming video service BlinkBox and is another building block in Tesco’s bid to build a paid content offering that appeals to its mass market, mainstream customer base. ‘Mass market paid content’ may be an oxymoron right now but if anyone is going to take paid content mainstream it will most likely be a mass market brand. And yet it will be far from plain sailing for Tesco.

Tesco’s paid content strategy is both aggressive and defensive.

Tesco has been aggressively – and in the main, successfully – pursuing non-grocery revenues for a number of years now. (Though a recent dip in overall revenues has seen a commitment to a renewed focus on core grocery products). Paid content is a product line which would clearly be new revenue opportunity for Tesco and music would be the obvious lowest common denominator hook for pulling consumers into a blended paid content offering. It is a strategy that has worked well for Apple and to some extent Amazon.

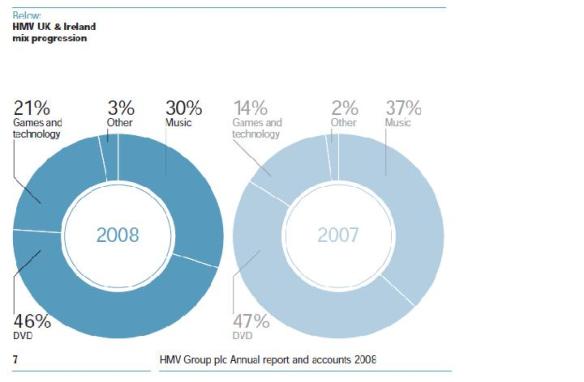

The role of Amazon brings us to the defensive play for Tesco. Tesco hasn’t always had the smoothest of relationships with the music industry, particularly the retailing element of it. Like supermarket chains in many other markets Tesco has pursued a strategy of loss leading with a relatively limited selection of front line and classic catalogue CD titles. Its aggressive pricing strategy has helped bring CD prices tumbling down (great for consumers, less good for record label margins) and it has sometimes tried to bend the rules to get stock cheaply (such as sourcing from Eastern Europe). Tesco does all of this because it helps footfall in store and because it helps migrate its customer base up the product ladder from baked beans, to CDs, to computers and so on. All of which is remarkably similar to Amazon’s strategy, the difference being that Amazon use CDs (and books and DVDs) as the entry point on the product ladder. As CD sales decline though the ability to use CDs as a customer acquisition hook diminishes. Amazon knows this all too well, hence its aggressive – but thus far only modestly successful – pursuit of an MP3 store strategy.Now Tesco can see the writing on the wall too.

Selling paid content from the supermarket aisle

The task is more robust for Tesco than it is for Amazon. All of Amazon’s customer relationships are digitized because it is an online retailer. Tesco though, despite being a global leader – at one time the global leader – in online retailing does not have a digital relationship with the majority of its customers transactions. As Amazon will attest, it is already challenging enough trying to persuade customers in an online environment to opt for digital versions of products even when they are positioned alongside physical versions and more cheaply. The task is nigh on impossible in a supermarket aisle. Which is where I think We7 will come in. It is a much more straightforward – though still not easy – task to get customers to visit a free online content destination, such as a streaming music offering, than it is to get them to dive straight into buying digital content.

A smart move for Tesco would be to use We7 to power a free music offering that is available only to holders of its Tesco Clubcard loyalty scheme. This would give customers another reason to opt into the Clubcard scheme if they haven’t yet, and for those that have it would give them reason to start engaging with it online. Once it has customers engaged with free streaming music Tesco then has a much easier task of migrating portions of those consumers to paid digital music, whether downloads or subscription. Tesco has a number of incredibly valuable assets at its disposal to promote usage in both a broad and targeted manner. For example users of the free streaming music offering could be given a free download with every £50 spent at the till. In store integration and promotion would be more challenging but various compelling options exist ranging from voucher cards to digital content bundled with CDs.

In short We7 could and should become the foundation stone of Tesco’s walled-freemium music strategy. Tesco have talked a decent digital music game for years now without notable success. A £10 million investment in We7 could well prove to be a very cheap pass to the big time.