Spotify’s Daniel Ek is betting big on developing a ‘two sided marketplace’ for music. With the company’s market cap on a downward trend despite strong growth metrics, Ek might find himself having to play up the disruption narrative more boldly and more quickly than he’d planned. Investors are betting on a Netflix-like disruptor for the music industry, rather than a junior distribution partner for the labels. And this is where it gets messy. Whereas Netflix can play individual TV networks off each other and can even afford to lose Disneyand Fox, each major record label has enough market share to have the equivalent of a UN Security Council Veto. So when Spotify announced it was going to let artists upload music directly and thenadded distribution to other streaming services via DistroKid,the labels understandably smelt a rat. To the extent they threatened to block access to India. Spotify’s balancing act may be reaching a tipping point (mixed metaphor pun intended), but it may already be too late for the labels to act. Here’s why…

In search of market share

If Spotify is able to become more competitive (and therefore threatening) to labels and keep hold of them, it will all be down to market share. The less market share the big labels have on Spotify, the more negotiating power Spotify has. It is a classic case of divide and rule. If Spotify really wants to play the role of market disruptor (and so far we have strong hints rather than outright statements), it will need to whittle down the power of the majors before they call it and pull their content. Here’s a scenario for how Spotify could achieve that.

1 – Direct indie label deals

The first step is detangling embedded indie label market share from the majors that distribute them and therefore wield their market share as part of their own in licensing negotiations. There are two ways to measure market share:

- By distribution (this includes indie labels distributed via major labels being included in the share of the bigger labels)

- By ownership (this measures based on the original label, so does not count any indie labels as part of major labels)

By the first measure, the major labels had an 82% market share in 2016 and 79% market share in 2017. By the second measure, according to the WINTel report, major label market share was 62% in 2016 (the 2017 WINTel number is not yet out but will be shortly). So, if Spotify does direct deals with the larger indies currently distributed by majors or major-owned distributors (or persuades them to join Merlin), it unpacks up to more than a fifth of major label market share.

2 – More artists direct

DIY artists uploading directly to Spotify is a long-term play, aimed at harnessing the potential of tomorrow’s stars. In the near term, these artists will generate a smallish amount of streams, even with a helping hand from Spotify’s algorithms and curators. There are about 300 artists right now; let’s say Spotify gets to 2,500 next year, it could potentially deliver around a third of a percent of share of Spotify streams.

3 – Library music

Fake artist gatesaw a lot of people getting very hot under the collar, but nothing that was done was against any rules. Instead library music companies like Epidemic Sounds were – and still are – serving tracks into mood based playlists. The inference is that Spotify is paying less for Epidemic Sounds tracks than to labels. Whether it is or isn’t, this still eats away at label market share on Spotify. With a bit more support from Spotify’s playlist engine, these could account for around 0.7% of streams. Coupled with artists direct, that’s a single point of share. Not exactly industry changing, but a pointer to the future, and a point of share is a point of share.

4 – Top 20 artists

Where Spotify could really move the needle is doing direct deals with top tier, frontline artists, probably on label services deals, as Spotify doesn’t appear to want to become a copyright owner – not yet at least. Netflix is funding its original content investments with around $1.5 billion of debt every two years, which it raises against its subscriber growth forecasts. No reason why Spotify couldn’t do the same, paying advances that other labels couldn’t compete with. The top 20 artists on Spotify account for around 22% of all Spotify streams. If Spotify could do direct deals with each of them and promote the hell of out of their latest releases, they could contribute up to 15% of all streams. Of that top 20, Taylor Swift is on the lookout for a new label, and Drake is putting out ‘albums’ so frequently that he must be pushing up close to the end of his deal.

When we add all these components together we end up in a situation where the major labels’ share of total streams would be just 47%. Spotify would have the second highest individual market share, while regional repertoire variations mean that SME and WMG could drop towards 10-11% in a couple of regions.

Of course, this is a hypothetical scenario, and one on steroids: the odds of Spotify signing up all the top 20 artists in the next 12 months is slim, to put it lightly, but it is useful for illustrating the opportunity.

Prisoners’ Dilemma

At this stage we move on to a prisoners’dilemma scenario for the majors:

- All of the majors help Spotify’s case by over prioritising Spotify as a promotional tool in light of its share of total listening compared to radio, YouTube, other streaming services etc

- WMG and SME probably couldn’t afford to remove their content from Spotify but would be watching UMG, the only one that probably feel confident enough to do so

- However, UMG would be thinking if it jumps first and removes its content, each of the other two majors would benefit from it not being there (and would probably be secretly hoping for that outcome)

- Each other major would be thinking the same, and regulatory restrictions prevent the majors from discussing strategy to formulate a combined response

- But even if UMG did pull its content, this would hurt Spotify but would not kill it (Amazon Prime Music launched without UMG and spent 15 months growing just fine until UMG came on board)

- Spotify could easily tweak its curation algorithms to minimise the perceived impact of the missing catalogue, making it ‘feel’ more like 10%

- So, the likely scenario would be each major paralysed by FOMO and so none of them act

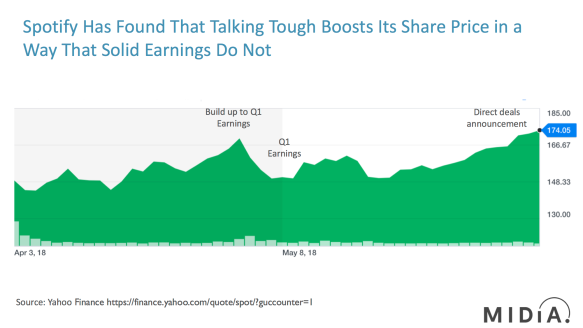

Thus, maybe Spotify is already nearly big enough to do this, and could do so next year. And the more that Spotify’s stock price struggles, the more that Spotify needs to talk up its disruption. History shows that when Spotify makes disruptive announcements, its stock price does better than when it delivers quarterly results. Maybe, just maybe, the labels have already missed their chance to prevent Spotify from becoming their fiercest competitor. The TV networks left it too late with Netflix…history may be about to repeat itself.