In recent days we have seen three major developments that, collectively, are a potential pivot point for social music:

- TikTok close to a US-entity buyout by Microsoft to avoid potential sanctions, following hot on the heels of an India blackout

- Facebook launched a (US-only) YouTube competitor for music videos

- Snap Inc signed a licensing deal with WMG and others, also for music videos

As cracks begin to appear in the audio streaming market, there is a growing sense in the music industry of the need for a plan B. This has been driven by growing discontent among the creator community, and a slowdown in revenue growth (UMG streaming revenues actually fell in Q2 as did Sony Music’s); the tail wagging the artist-and-revenue (A&R) dog. The search for new growth drivers is on, and social music – for so long a promise unfulfilled in the West – is one of the bets. TikTok was meant to be a major part of that bet. But with the US future of the app so at risk that a Microsoft US-entity buyout may be the only option, and the continued impact of COVID-19 on core revenue streams, the future is beginning to look a little more troublesome. Perhaps now more than ever, the music industry needs social music to start delivering.

There are three key issues at stake here:

- How consumers discover music

- How (particularly younger) consumers engage with music

- Competing with YouTube

How consumers discover music

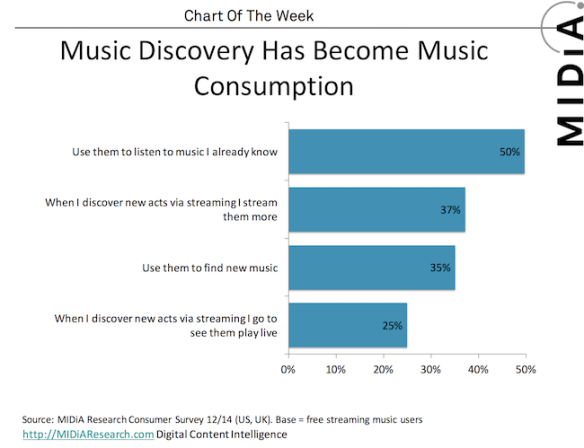

Among the under-aged 35 demographic, YouTube is the primary music discovery channel, followed by music streaming, then radio, and only then by social. Streaming discovery is heavily skewed towards tracks and playlists, and away from artists and release projects, which is fine for streaming platforms but impedes building sustainable artist careers. Radio is losing share of ear and YouTube… well, YouTube is YouTube (more on that below), so the music business needs a new discovery growth driver. Social has the potential to be just that. But spammy artist pages on Facebook and more-than-perfect Instagram photos are not it. TikTok, for all its amazing momentum, actually has a really uneven impact on discovery. Some tracks blow up out of nowhere while most do little, and rarely is it because of a smart label marketing strategy but instead because certain tracks just work on the platform and the community leaps on them. For now, TikTok is too unpredictable to plan around. Facebook (Instagram especially) and Snap Inc have a fantastic opportunity to do something special here. They have the audience and the social know-how. Whether they can deliver is a different matter entirely.

How (particularly younger) consumers engage with music

What TikTok lacks in consistent marketing contribution it makes up in consumption. Following on from Musical.ly’s start, TikTok has reimagined how music can be part of social experiences for young audiences. It has made music a highly relevant and integral part of self-expression, something that CD collections and music dress codes used to do in the pre-digital world but that soulless, ephemeral playlists wiped out. While labels pin hopes on TikTok successes to drive wider consumption, the discovery journey is also the destination for most TikTok users – they hear the track in a video and swipe onto the next one. That is no bad thing. This is a new form of consumption, and if TikTok were to disappear or fade then someone else needs to pick up the baton. Whether Facebook and Snap Inc can do so is, again, an open question.

Competing with YouTube

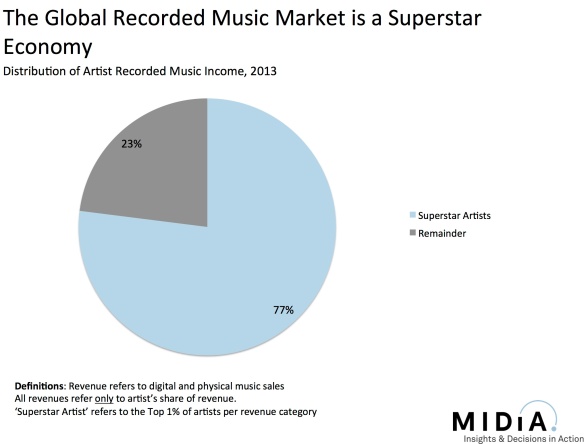

Now we get to the heart of the Facebook and Snap Inc deals. As important as the previous two points are, they were not the overriding priorities of the commercial teams driving these deals. Instead they were focused on expanding the revenue mix and part of that is creating more competition for the notoriously low-paying YouTube. Well, maybe not that low paying after all.

The internet is full of statements from trade associations, rightsholders and creators about how much less YouTube pays than Spotify. YouTube does pay less, because it manages to escape paying minimum per-stream rates for ad-supported videos – but it is a more nuanced picture than lobbyists would have you believe. Firstly, in terms of its Premium business, Google is entirely on par with Spotify. But then, that is the part that is licensed in the same way as the rest of the market.

Ad-supported is a mixed story. In North America, where there is a mature digital ad market, YouTube’s ad-supported average revenue per user (ARPU) is entirely on par with Spotify’s. However, on a global basis, ad-supported ARPU is dragged down by its large user base in emerging markets where digital ad markets are nascent. Spotify’s ARPU is 66% higher, in part because it has to pay minimum per-stream rates, i.e. it pays a fixed rate per stream regardless of whether it has sold any ad inventory against the track. This boosts ad-supported ARPU but it risks making the model unstainable, to the extent that Spotify reported -7% gross margin for ad-supported in Q1 2020 (and note, that’s gross margin, not net margin).

Rightsholders will be hoping for Facebook and Snap Inc to bring a similar level of competition to music video as exists in streaming audio, which in turn may give them a path to higher global ad-supported ARPU rates and a healthier marketplace. However, what will determine that objective is not business strategy but product strategy. The key question is what can they both do with music videos that YouTube cannot? YouTube has years of experience and user data around music videos, Snap Inc and Facebook do not. They will be playing catch-up with a weaker portfolio of content assets: Snap Inc is only partially licensed and both it and Facebook have only licensed official music videos. Unofficial videos (mash ups, covers, lyrics, TV show appearances etc.) account for 25% of the views of the top 30 biggest YouTube music videos. Those videos are crucial in that they provide the lean-forward element for viewers; they are crucial to making YouTube music social rather than just a viewing platform.

YouTube has dominated the music video globally for more than a decade. This might just be the time that this position starts to be challenged. But if Facebook and Snap Inc are going to do that, they will have to bring their product strategy A-game to the field. If they can, then the we may indeed witness a social music turnaround in the West.

Crowdmix was one of those start ups that promised to change the world. It was going to be a social network focused around music that would transform how people discover music and how audiences and influencers interact.

Crowdmix was one of those start ups that promised to change the world. It was going to be a social network focused around music that would transform how people discover music and how audiences and influencers interact.